Just as fast food chains have fueled Americans’ hunger for more, bigger, faster when it comes to what we put in our bodies, fast fashion brands increasingly beguile shoppers the world over with options of what to put on our bodies. Over the past decade, rapidly made garments – sold at low prices and manufactured at even lower price points – have proliferated shopping centers across the nation. In some fast fashion shops, consumers can even buy an outfit for the price of a Happy Meal.

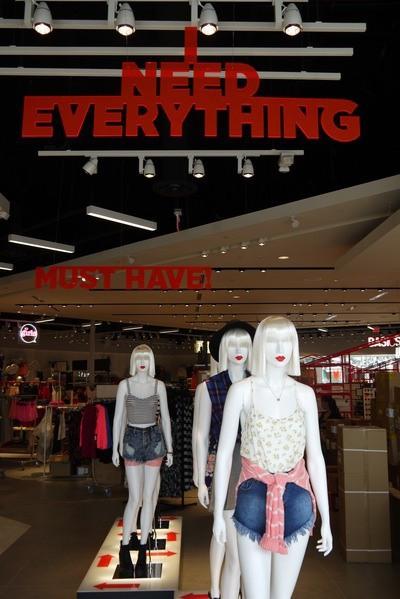

Consumers’ fascination with stores such as Forever 21, H&M, Uniqlo and Zara isn’t rocket science – who wouldn’t want to buy the latest trends for a fraction of the cost? Why pay $100 for a sweater, when you can get a near-replica for only $25? That’s how most shoppers understand fast fashion.

And that’s why earlier this year, fast fashion forefather Forever 21 opened the concept test store F21 Red, which boasts starting price points as low as $1.80 (selling $3.80 T-shirts, $5.80 leggings, and $7.80 denim jeans). Consumers are eating it up. Fast fashion is a multi-billion dollar industry, and it’s growing. Already, Forever 21 operates 600 stores worldwide – and the company plans to double its global presence by 2017 – while Zara has 1,800 locations and H&M owns 3,400 stores. Annual revenue for those companies has risen by the billions in the past years, a significant contrast to the slow decline of the traditional apparel retail market.

Rather than follow the traditional apparel model of selling seasonal lines of clothing, manufactured and marketed months in advance, these bargain brands rapidly respond to the latest fashion trends, quickly address consumer demands, and live by just-in-time production. As a result, consumers get more, faster: A fast fashion shopper can get a dress, two scarves, a shirt and pants for the price of only one sweater from a traditional retailer.

While this model may be good for consumers’ pocket books and closets, incidents such as the collapse of Rana Plaza and the unnaturally dyed polluted rivers of China have shown that making clothes using low-cost labor in environmentally unregulated developing countries can come at great costs. What is the antidote to this apparel paradox?

In response to public scrutiny and pressure from activist groups – take Greenpeace’s Toxic Threads campaign or Clean Clothes Campaign's ongoing petitions – some fast fashion brands are increasingly addressing social and environmental supply chain concerns. For example, after public pressure ignited by Greenpeace’s Detox campaign, Zara committed to eliminating all hazardous chemicals from its supply chain and clothes by 2020. And after the Rana Plaza collapse, Zara, H&M and other fast fashion brands signed the Accord on Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety in hopes of avoiding future disasters.

In some cases, brands are moving beyond simply responding to crises to proactively developing sustainability strategies. H&M, for example, launched a Conscious Collection made from recycled fibers and organic cotton, and through its Don’t Let Fashion Go to Waste campaign the company invites shoppers to bring in their used clothing into stores for recycling. The Swedish retailer has also pledged to pay living wages to textile workers in factories in Bangladesh and Cambodia that make its clothes, and has made its supplier list public to increase supply chain transparency. All steps in the right direction – but is it enough?

Advocates of slow fashion think not. A parallel to the slow food movement, slow fashion promotes the making of high quality garments – often handcrafted clothes that are meant to last for more than one season – using locally grown materials and resources. An alternative to the mass-produced, disposable fashions of low-cost retailers, slow fashion startups such as Zady, Everlane and Cuyana espouse "fewer, better" instead of more and faster.

Will shops like Forever 21, H&M or Zara ever be able to fully slow down, all while meeting consumers’ voracious appetite? Perhaps the question should be: should they slow down? If fast fashions brands promise to make their clothes more responsibly, is that enough? Can we live in a world where a more sustainable version of fast fashion and slow fashion can happily coexist? We’d love to hear your thoughts, please share them below.

Nayelli is the Founder & CEO of CreatorsCircle, a resource hub that connects diverse youth with opportunities to create a life of purpose and impact. A trained journalist with an MBA, she also keeps the pulse on sustainable business and social impact trends and has covered these topics for a variety of publications over the past 15 years. She’s a systems thinker who loves to learn, share knowledge and help others connect the dots.