Editor’s Note: This post is part of a student blogging series on The Business Of Sports & Sustainability. Students attend the Presidio Graduate School which offers the only MBA-level sustainability program focused exclusively on the sports industry. You can follow the series here.

By Marty Meisler

There’s nothing quite like the smell of freshly-cut grass, or the look of a well-manicured ball field. Ask any 5-year-old, grass is the quintessential playing surface! Despite this, artificial turf (turf) is rapidly replacing grass as the surface of choice for sports facilities at all levels. Where community parks, schools and stadiums were once the exclusive domain of grass, roughly 11,000 turf fields are now in use in the U.S., and the industry expects double-digit annual growth.

Many of these facilities switched to turf on the promise of lower maintenance costs, reduced injuries, water savings, elimination of chemicals, year-round access, improved playability and durability. Some of these fields, however, have been switched back to grass, and some, back again to the latest third-generation turf.

All of which begs the question: Which is better, plant or plastic? As always, better depends on your perspective. From a sustainability perspective, an assessment of “better” should consider impacts to people and planet, in addition to the cost and convenience factors identified above. While a lifecycle analysis is beyond the scope of this post, a review of some important considerations that might be included is provided.

Artificial turf: Background

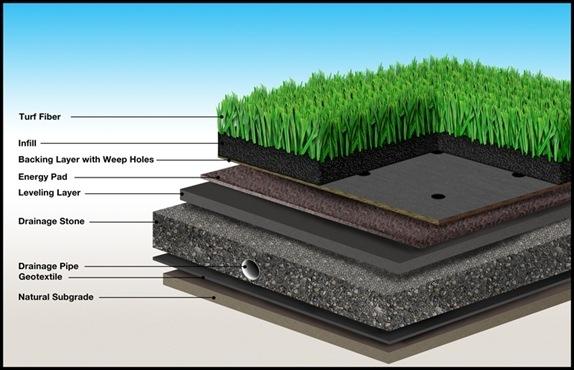

Artificial turf first hit the big leagues in 1966; Monsanto’s Chemgrass (later changed to Astroturf) was installed in the Astrodome after painting the glass roof to reduce glare for the athletes resulted in insufficient light to sustain the grass field. Turf has evolved significantly: from that simple plastic carpet installed on dirt or concrete, to a complex product comprising multiple layers of petroleum-based polymers and drainage systems. The illustration above shows a typical advanced turf system that might be installed in a collegiate or professional stadium, although every product is different.

The innovation most likely responsible for turf’s widespread acceptance was the introduction of infill, used between the blades to provide a more cushioned surface.The most common infill materials are crumb rubber, made from ground-up car and truck tires, or a combination of crumb rubber and silica sand. It is estimated that crumb rubber, also used for cushioning on playgrounds, is responsible for diverting 50 percent of used tires, which might otherwise end up in landfills or incinerators.

Concerns with turf

Three main concerns should be considered in purchasing decisions when assessing the sustainability of turf: exposure to chemicals in the crumb rubber infill, the heat-island effect and disposal at the end of usable life.

Safety of crumb rubber infill: Prompted by a report of a cancer cluster among young soccer players, especially goalies, the EPA conducted a “limited-scale” study on crumb rubber. The inconclusive study identified 30 compounds or materials that may be found in tire rubber, including carbon black, lead, mercury, benzene and halogenated flame retardants that would also be present in crumb rubber. Tires are considered to be hazardous waste in some states, and some of these constituent chemicals are known to be toxic or carcinogenic.

Heat-island effect: As a plastic product with dark rubber infill, turf gets really hot on warm days. It is not uncommon for temperatures to be 40 to 50 degrees Fahrenheit above that of adjacent grass fields. The record reported temperature was 200 degrees on a 98-degree day. Higher temperatures, in addition to posing a health risk, also increase the off-gassing of volatile chemicals from crumb rubber. Spraying water on the field can help mitigate the heat.

Disposal: Constituents of turf include polyethylene, polypropylene, nylon, styrene butadiene rubber and polyurethane, which are theoretically reusable or recyclable, if the turf is deconstructed to separate the materials. Currently, this cannot be done onsite, and shipping costs are generally prohibitive. As a result, most turf is either landfilled or incinerated at the end of its eight- to 10-year life. The volumes are staggering. The Synthetic Turf Council estimates that by 2017, over 1,000 turf fields will be replaced annually. A typical sports field is roughly 80,000 square feet, consisting of 400,000 pounds of infill and 40,000 pounds of turf. For 1,000 deconstructed fields, that totals 80 million square feet of turf weighing 40 million pounds, along with 400 million pounds of infill. Landfilling one field’s worth generally costs $30,000 to $60,000.

Issues with grass

I don’t want to give the impression that grass is without its faults. Like other monocultures, grass requires a lot of maintenance: mowing, as well as large quantities of water and chemicals, including fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides -- all with associated environmental impacts that include greenhouse gas emissions from petroleum use and manufacture of chemicals, contamination of waterways from storm water run-off, production of methane gas if trimmings are landfilled, and potential exposure to these chemicals.

Benefits of grass

On the other hand, the benefits of grass playing fields include infiltration and treatment of storm water, carbon dioxide capture and production of oxygen, cooling of surrounding areas through transpiration, and habitat for a variety of organisms. For athletes, grass is a naturally forgiving surface.

As the father of a budding soccer superstar, in addition to considering turf’s sustainability, I find myself even more concerned with potential health effects and wonder whether my superstar should play on artificial turf at all. I’m inclined to follow the precautionary principle until turf is proven to be safe for children as well as the environment. What are your thoughts?

Image credit: Used with permission of the Synthetic Turf Council

Marty Meisler is currently pursuing an MBA in Sustainable Management at Presidio Graduate School. Marty has a Ph.D. in biology; professional experience in water and residential green building; and interests in biomimicry, entrepreneurship, sustainable wine, and chasing soccer balls.

This “micro-blog” is the product of the nations first MBA/MPA certificate program dedicated to sustainability in the sports industry. Led by Dr. Allen Hershkowitz, Senior Scientist at NRDC, The Business of Sports and Sustainability certificate is housed at Presidio Graduate School, the nation’s top sustainable MBA program. Posts explore the connection of sustainability with operations, branding and fan engagement of the sports industry including leagues, teams, venues, sponsors, vendors and surrounding communities.