Collectively, the senior leadership of corporate America does not resemble the country they are supposed to serve. As a consequence, too many of the mistaken assumptions about people of color still hold sway, making it difficult for people of color to advance in those environments.

Errol L. Pierre, a corporate executive in the healthcare industry, believes people of color must, and can, find ways to turn those assumptions to their advantage.

“If we turn what we think are these weaknesses to our strengths and find value in knowing that being unique is great and you don’t want to be like everybody else, it becomes something that you can leverage to help you grow and to help you distinguish yourself from everybody," Pierre told TriplePundit.

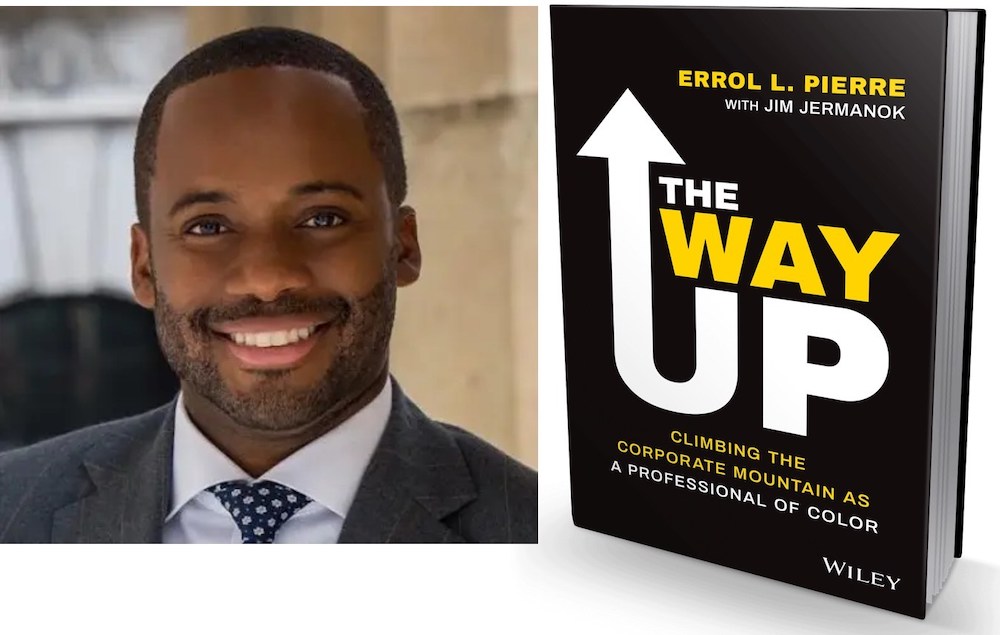

Pierre describes this strategy for advancement and many others in his first book, "The Way Up: Climbing the Corporate Mountain as a Professional of Color," which he intended as a guide to help underrepresented individuals from all ethnic backgrounds to reach their professional goals.

A critical element in countering those assumptions, Pierre told us, is not to hide your background and your unique experiences.

The son of Haitian immigrants, early in his business career Pierre didn’t share much about his life away from the workplace, such as mentioning he attended a Haitian festival because “it was out of the norm and didn't fit in with what the other people were doing.”

"Now, I use the things that I’ve gone through on my path and the nuances of being black in America coming from immigrant parents as strengths,” Pierre said. "If you are in a mid-level position and you happen to have a unique background, a different ethnicity, share your story because you will never be forgotten. If you share your story with an executive that you bump into an elevator or when you meet them on a call, they will remember you. That’s how you differentiate yourself."

Pierre, who is senior vice president of state programs for the not-for-profit health insurance company Healthfirst, said that although it can be daunting, underrepresented people must use their strengths to counter the microaggressions and bias they encounter.

"I remember walking into a conference room . . . with three other white employees to meet with a client, and the client immediately assumed someone else was the lead person," Pierre remembered. "Absolutely, these assumptions turn into one thinking that people will treat you a certain way, not even realizing who you are. These become like 100 paper cuts that add up to pain, dejection and disempowerment, which also leads to people to not even want to try."

Pierre worked on "The Way Up" during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. His initial motivation had been his feelings in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd. That motivation shifted as he realized the pandemic was having a disproportionate impact on black and brown communities.

"As stories became more focused on the reasons for these disparities, not just in health, not just in income, but also in corporate America, I thought, 'Well then, what can I do to try to help address it?'" Pierre explained.

"The Way Up" underlines the problems people of color face in corporate America. Some have said it excludes white people, but Pierre is surprised by that reaction.

Pierre said he has a "whole library of leadership books" that he learned from, but he never saw himself in them. Throughout "The Way Up," he credits white colleagues and mentors who have helped and encouraged people of color to seek closer connections to corporate leadership.

"I was surprised that people would take it that way, that I was excluding white people,” Pierre said. “If they read the book, they would realize I talk about many white people that helped me in my career, so there was no intention to exclude anybody."

More common is the positive reaction "The Way Up" has garnered thus far, with people writing to thank Pierre for sharing his tips for success and for being "vulnerable."

"That's how much it resonates with people, and I’m so glad that it is," he told us. "They felt like they didn’t have a leadership book out there that spoke to them. And the whole intent was to have a leadership book that speaks to people who feel underprivileged, underrepresented, undervalued, and I’m glad it’s reaching that market."

Image credits: Vasyl/Adobe Stock and Errol L. Pierre

Gary E. Frank is a writer with more than 30 years of experience encompassing journalism, marketing, media relations, speech writing, university communications and corporate communications.