PlanetCare's filter attaches directly to a washing machine's drain hose to capture the microfibers released from clothes when doing laundry. (Image courtesy of PlanetCare)

The term microplastics often conjures images of plastic bags and bottles breaking down in the ocean. But it isn’t just decaying litter that creates the minuscule pieces now found in every part of the planet — including human bloodstreams. The bulk of products that make up modern life add to the microplastic problem.

Microplastics make a huge problem

“Just by doing our laundry, the amount of microfibers we throw into the oceans is the same as if you would take a plastic bag and throw it into the sea,” said Marjana Lavrič Šulman, chief brand officer at PlanetCare, a company that makes washing machine filters to capture these fibers. She’s not talking about one bag per year. For the average household, doing laundry is the same as tossing a plastic bag in the ocean every week.

“You would never do that,” she said. Not on purpose, anyway. But the difference is what we can see and what we can’t. “[When] doing your laundry, you don't see it, but the amount of plastic is the same. So, every single user that we managed to onboard basically does not throw 52 plastic bags per year into the ocean.”

The equivalency is startling, to say the least. But it hasn’t been enough to get the industry to act. “Originally PlanetCare started with an integrated filter for washing machine manufacturers,” Šulman said. The company pitched that design to manufacturers in 2017, only for founder and CEO Mojca Zupan to be told that she would be better off adopting a dolphin.

Pivoting to consumers

“The hardest lesson was to realize that there are no quick wins, even though you think you have a great product that solves a very serious problem,” Šulman said. “The industry just doesn't care. And for us to be resilient enough to show that, then you change the business model. Then you go to the end consumers. Then you turn to those who do care.”

PlanetCare’s first aftermarket filter launched in 2019 and has 7,000 users worldwide. It’s an impressive number for a startup that doesn’t have an advertising budget, access to venture capital or corporate partners. Instead, the company relied on an EU grant and funding from a family in its home country of Slovenia. “We’re really actively searching for investors,”Šulman said.

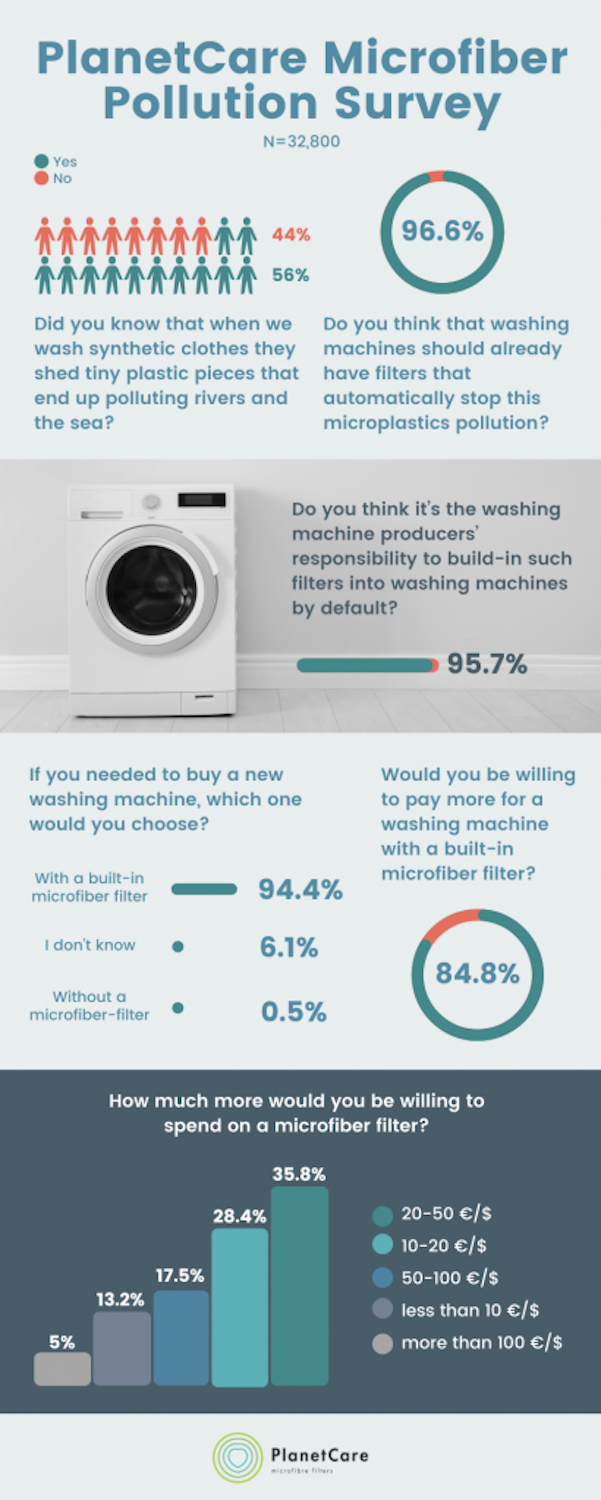

That search includes a successful crowdfunding campaign aimed at its second-generation filter — PlanetCare 2.0. Pledges are far outweighing the company's original goal, which goes to show a significant number of people are interested in doing the right thing when it comes to microplastics. Additionally, a survey conducted by the company in 2021 found that almost 85 percent of respondents would pay more for a new washing machine with a built-in microplastic filter versus a machine without one.

“After four years, we have now made it better,” Šulman said of the upgraded model. “It's hardly the same filter. We say it's an improved version of the first one, but really everything's new. Everything's different.”

The PlanetCare filter attaches directly to the drain hose, doesn’t require any electricity to run and is compatible with all washing machines. Independent testing shows that PlanetCare 2.0 captures 98 percent of fibers, though variation is expected with different machines and cycles and will also depend on what is being washed.

A need worth meeting

While it is disappointing that manufacturers were not interested in the original integrated filter — nor fair for the industry to continue to shift responsibility to the consumer — there is a definite need for aftermarket filters for microplastics. In 2013, 840 million washing machines were in use worldwide, according to the latest available data. More are certainly in use now, and it will be a long time before they all need replacing.

As with the shift to electric vehicles, upgrading before an appliance has worn out just to get one with an integrated filter would do more harm than good. In this respect, PlanetCare has the potential to fill an enormous need as hundreds of millions of machines could use the external filters. The issue is making it happen, especially in poorer and more remote regions.

Another benefit to PlanetCare’s external filters is the closed-loop system. Used filter cartridges are sent back to the company where they are cleaned, refurbished and redistributed. The microfibers are collected for recycling. At this point, the pool is too small to have any products on the market that are made from them, but the company’s pilot program has produced insulation mats and mesh for chairs.

The new model features a much more efficient cartridge than the first, Šulman added, and the cartridge filters fill up in about four weeks with average use.

While there is a carbon cost to shipping the filters back and forth, asking the consumer to wash and reuse their filters at home would send the fibers into the water system anyway — defeating the purpose altogether.

“We know this is a pain of ours, that sending the cartridges back and forth is not really the most environmentally-friendly thing we can do,” Šulman said. “That's why for those really far-away users, we say, ‘Please don't buy the small starter kit with only three spare cartridges. Get the large one and we only have to do it once per year.’”

The company has a clear vision for the future that includes local refurbishing units, so it won’t be necessary to send the cartridges back to Slovenia. “Once we have 5,000 users in Australia there will be a local unit, or once we have 5,000 users on the West Coast, or on the East Coast, or anywhere in Europe,” Šulman said. “It's an easy, very easy system.”

Patagonia has leveraged its brand recognition with appliance maker Samsung to develop an external microplastic filter, too. As a producer of outdoor clothing and gear, Patagonia’s products rely heavily on synthetic fibers that shed microplastics — which is what prompted the company to form the partnership two years ago. Samsung also introduced a "less microfiber" cycle that it says can be downloaded as an update to any of its machines. Still, it begs the question: Why aren’t manufacturers more motivated to include integrated filters on all new machines?

“I was naive five years ago, and I actually thought there would be somebody who would just do it because it's the right thing to do. Because we all live on the same planet, and we all use the same resources, and we all drink the same water,” Šulman said of the industry’s lack of interest in building models with filters already installed to remove microplastics. “But I still hope the filter gets integrated without the regulative pressure.”

Images courtesy of PlanetCare

Riya Anne Polcastro is an author, photographer and adventurer based out of Baja California Sur, México. She enjoys writing just about anything, from gritty fiction to business and environmental issues. She is especially interested in how sustainability can be harnessed to encourage economic and environmental equity between the Global South and North. One day she hopes to travel the world with nothing but a backpack and her trusty laptop.