India has an agriculture economy, with more than 54 percent of the country's land classified as arable. The sector provides livelihoods to over 151 million people, and about 60 percent of the Indian population works in the industry, contributing to 18 percent of India's GDP.

Despite the significance of the sector in India, farmers have a low household income of INR10,000 a month on average, or about $120. Farmers with less than two hectares of land are referred to as small and marginal farmers, and they comprise about 86 percent of India’s total farmers. A recent study reveals that nearly 70 percent of marginal farmers in 20 Indian states engage in non-farm activities to supplement their agricultural income.

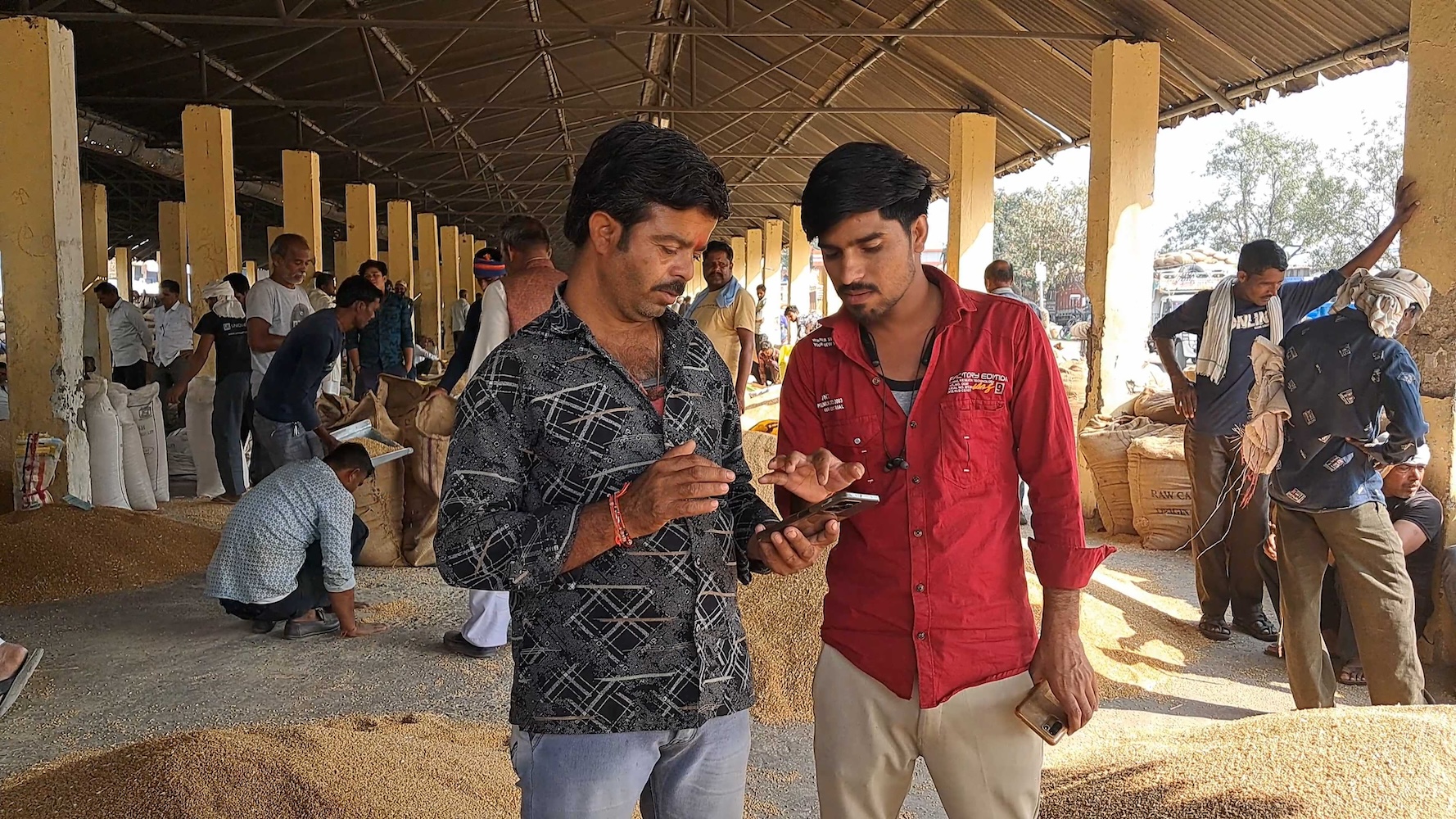

Farmers, especially in rural India, face many challenges to sell their produce. These include difficulty in accessing financing, insufficient storage facilities for their produce, and underdeveloped roads that hinder transportation of their yield to market.

These gaps, alongside inflation, add to the cost of production and limit farmers’ ability to fetch fair prices for their produce. Around 28 percent of farmers earned less than the expenditure they incurred to grow the crop, according to research conducted by the agri-tech social enterprise Gramhal.

“Small and marginal farmers, who form the majority of farmers in India, are not part of the country’s formal credit system,” said Simeen Kaleem, co-founder of Gramhal. "They take loans from middlemen, or what we call ‘aggregators,' who buy produce from multiple farmers and take it to market."

Gramhal has an underlying mission to increase the income of Indian farmers and has worked with a quarter of a million farmers over the past three years.

“These aggregators are ‘all-weather’ friends of farmers. If there is a family wedding or an emergency hospitalization and the farmer needs money, they are the ones giving the loan," Kaleem said. "This feeds into the problem where when a farmer is selling to these aggregators, their ability to negotiate doesn't exist. So, it is a complicated relationship of power and dependence between the farmer and aggregator.” In addition, farmers do not have access to market information, so they have no idea how to properly price their goods.

“Most farmers usually get information from the aggregators who have sold the crop, or directly from the buyers," Kaleem said. "Any other data sources accessible, like from the government or from small local shops (called mandis), are unreliable with incomplete information. So, there is no way for most farmers in India to get real-time market pricing information to be able to make a selling price decision for their produce."

The lack of access to market price information and reliance on intermediaries to sell on their behalf leaves farmers vulnerable to price exploitation and uncertain returns on their investments.

To solve this, Gramhal is building a data cooperative in India where farmers contribute their information to a data ecosystem, which all farmers can leverage for better informed decision-making.

“We are trying to bridge the information divide,” Kaleem said. “If you're a farmer who has the ability to go to market, you should have market price information from all markets around you so that you can decide which one is giving you a better price, and which one you want to sell at. That way, when a wholesale buyer or aggregator comes to your home, you know that, for example, the market price for maize is INR2200 per quintal, so you are in a position to negotiate the selling price of your product to the buyer.”

Gramhal has a five-year vision to empower at least 10 million farmers with full control over their data, granting them collective agency to make better decisions and achieve a 100 percent increase in income, all while transitioning to sustainable farming practices.

The social enterprise started the project to democratize data first by using the Indian government’s collected data sets from markets and crops across the country. It then built a chatbot (called Bolbhav) and plugged in that data. Soon about 300,000 farmers were accessing this data set via the chatbot on their mobile phones.

“We spent no money on marketing — this was all just from word of mouth!” Kaleem said.

However, Gramhal started getting feedback from farmers that the chatbot was giving them prices three days old and what they wanted was real-time, reliable data. “That is when we realized that we need to work with the power of community and think about a societal network framework where every farmer who is selling can contribute to the data and have access to it," Kaleem explained. "We needed to find a way where the farmer can send price information about what they are selling by uploading their receipts, and we can aggregate that data across markets and share it with them."

The solution was an upgraded version of the chatbot called Bolbhav Plus, which Gramhal launched in April 2023.

“In the last few months, we have had 16,000 people across eight markets log into our data via the app," Kaleem said. "Over 800 farmers have contributed to the platform with their own data, and 2,600 have paid a subscription fee to access this data.”

The platform is agnostic to the type of crop, fruit or vegetable. To incentivize farmers to contribute their data, Gramhal introduced a reward system where farmers can earn redeemable tokens if they upload their receipts, and then use the app at no cost.

“What we're trying to do is build this strong societal network where every farmer who has a data set contributes it into a data ecosystem that other farmers can leverage,” Kaleem said.

So far, over 120,000 receipts have been uploaded to the app, over 600,000 tokens have been earned, and about 500,000 tokens redeemed.

“If you're a farmer, for the first time now you have the same data from the market that the buyer has," Kaleem explained. "Symmetry and information between buyer and seller, and power to negotiate, ... has increased a lot. And farmers are making more money because they're able to negotiate better.”

User feedback from the app shows that farmers were able to earn an 81 percent higher income on average — about INR13,800 or $166 more. Gramhal estimates that the chatbot solution delivers INR10 in value to farmers against the INR1 they spend on running the chatbot.

“Doing this for the market price of crops is just one use case," Kaleem said. "Our app has the potential to become a one-stop platform where farmers receive all the information they need. In the coming months, we hope to add more information layers that will help the farmers further enhance their practices and income."

The organization is also working on a new solution that incorporates voice recognition powered by artificial intelligence (AI) so that farmers can ask their queries by speaking into the app. The prototype for this solution, called Matar, is currently being piloted by mushroom farmers in the Indian state of Bihar.

(Images courtesy of Gramhal)

Abha Malpani Naismith is a writer and communications professional who works towards helping businesses grow in Dubai. She is a strong believer in the triple bottom line and keen to make a difference. She is also a new mum, trying to work out a balance between thriving at work and being a mum. In her endeavor to do that, she founded the Working Mums Club, a newsletter for mums who want to build better careers and be better mums.