Fresno, California, has some of the highest levels of air pollution in the United States and is among the cities set to see a green economic boom thanks to federal climate programming. (Image: John/Adobe Stock)

Climate advocates celebrated the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency last month as it announced a closely watched $20 billion in grants under the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. The money will go toward nonprofits, state and local agencies, and community-based financial institutions so they can help finance infrastructure projects that reduce emissions, with a focus on communities that are historically underserved.

Advocates described the infusion of climate financing as "momentous," "groundbreaking" and "transformational" in interviews with TriplePundit last month. But some onlookers are still fuzzy about what exactly the grants will be used for, what they'll mean for communities and what happens next.

With grant financing set to be delivered this summer, we're taking a closer look at how the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund will translate into a domino effect of green infrastructure in communities facing outsized impact from climate change and pollution.

"A chance to rewrite history"

Low-income communities and communities of color face some of the worst air pollution in the United States, contributing to higher rates of preventable illnesses.

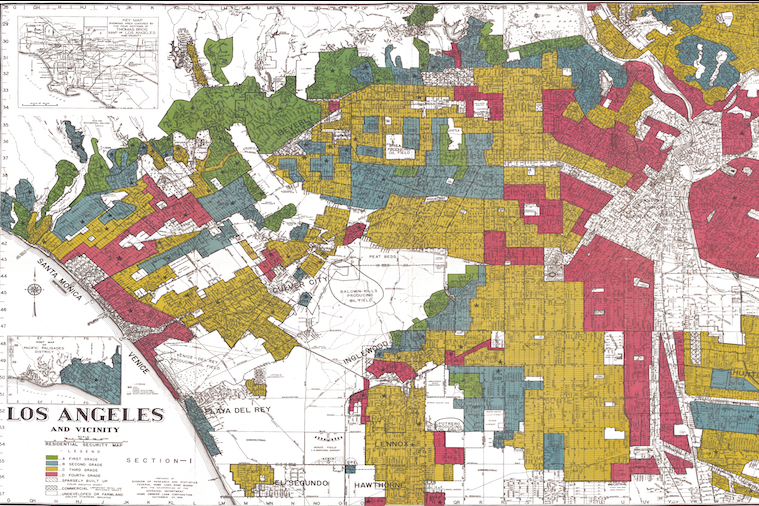

The financial practice of redlining is among the factors that contributed to this deadly legacy. As federal housing loans became available under the New Deal in the 1930s, government lenders and banks deemed certain neighborhoods — with predominantly Black and immigrant populations — too "high risk" to serve. That translated into red lines drawn around entire communities that could not access home or business loans because of where they lived, even if they personally qualified for credit, until the practice was outlawed in 1968.

Along with economic depression that's still visible today, many previously redlined neighborhoods tend to have higher levels of air pollution and greater proximity to oil and gas wells.

In many ways, the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund aims to flip this discriminatory financial model on its head to solve the problem. The recipients of the April grants are coalitions of lenders, so they won't build new solar energy installations, energy transmission lines or zero-emissions trucks themselves. They'll finance them within the regions they serve, and a mapping program specifically incentivizes them to focus on historically underserved communities that are overburdened by pollution.

"An inclusive green economy can create the economic opportunity that might be able to help us rewrite history from a financial institution perspective," said Jessie Buendia, vice president of sustainability for Dream.Org and national director of the Green For All program, which consulted with the EPA on developing the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund framework. "We're going to be able to target specific communities, many of whom were communities that were redlined historically, with an infusion of capital to build [green] infrastructure projects so they'll have the benefits associated with them — not just for jobs, but also for health."

With this financing, the Joe Biden administration aims to kickstart new green lending networks that can get projects built faster and attract private investment to multiply impact. It's not about the next big moonshot climate technology. It's about increasing access to systems that are already proven to reduce pollution, cut emissions and lower energy costs. Those include everything from community solar programs that allow renters and low-income households to share in solar power, to energy-efficiency upgrades for homes and businesses, to zero-emissions transportation and clean energy infrastructure.

"The technologies have already been proven in the market," Buendia said. "So, the innovation here is really going to be focused on deployment: How do you actually get these proven technologies into communities that have never had them before?"

A financial backbone for the Inflation Reduction Act

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund is only a small part of the broader Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which includes billions in tax incentives and grant awards for green infrastructure. Other grant competitions in the Inflation Reduction Act focus on stimulating a range of projects, such as expanding access to clean energy in rural communities, replacing diesel trucks with zero-emission vehicles, and reducing air pollution at ports.

The financing mechanisms established through the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund serve as a backbone for bringing the projects coming out of other Inflation Reduction Act climate programs to fruition.

"Because the Inflation Reduction Act has started making awards in all of the other programs, we actually have a huge need for financing and loans," Buendia said. "In government, you often work on a reimbursement basis, so you have to have money to get money."

In other words: As nonprofits, communities and businesses are awarded grants to implement their proposed projects, they'll need seed money to get started before various rounds of federal funding come through. The financial institutions within the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund are now ready and able to provide it, which can speed up the notoriously sluggish process of getting projects built.

"In the world of infrastructure, which I've worked in my whole life, you lose momentum and visibility — an opportunity to engage the public, an opportunity to celebrate these wins — because projects take so long to get online," Buendia said. "Being able to get a line of financing infused at this moment means that projects will be able to start earlier and hopefully get done earlier, and I think that's going to help build credibility for this type of investment in this country. It's really about how all of these different pieces of the Inflation Reduction Act begin to work together in a community."

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund at work in Fresno, California

To understand what all this means in practice, look no further than Fresno County, California, which faces some of the highest air pollution levels in the United States. The majority of Fresno residents are people of color, with over half identifying as Hispanic or Latino, and median household income is more than $20,000 less than the California average, according to U.S. Census data.

The city received EPA funding under the Inflation Reduction Act to develop a plan to build more green infrastructure. "Once they receive these federal grants, they're not going to have the money to begin the work, and that's where the [Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund] can come in," Buendia explained. "The municipality has identified their high-priority needs for an energy transition. They've identified perhaps developers who actually want to come in and provide those services. They've identified grant funding and capital that will finance it, and now they're going to need this infusion of funding to be able to get the actual work started."

Since $20 billion is nowhere near enough to finance the infrastructure needed for the low-carbon energy transition, a key objective of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund is to multiply federal investments by attracting private capital. In cases like Fresno's, the upfront work done by the community makes it less risky and more appealing for businesses to invest in the green infrastructure the community identified.

"We are really dealing with a trillion-dollar problem with climate change and climate mitigation. But the $20 billion downpayment the federal government is making will hopefully unlock other private-sector investments to the communities who need it the most," Buendia said. "What is game-changing is that communities like Fresno have not been targeted in the way that San Francisco, New York City, Los Angeles or these large markets have. They haven't been areas that are considered investible. Now, there's actually infrastructure for people to be able to get these projects online."

Grants are just the beginning

Beyond federal involvement serving to de-risk projects for private investors, the fact that Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund recipients represent networks of community-based lenders from across the country opens up doors for financing models that didn't exist before. That includes interstate projects for things like energy transmission infrastructure, or funds that allow private investors to put large sums into multiple projects and communities.

"The private sector often has a challenge with investing small amounts of money," Buendia explained. "They really want to figure out how to invest in the aggregate. The [Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund] program, working with the national applicants, that's going to be their job to figure out how to make it easy for the private sector to invest in these communities."

The program is meant to last long after the grants stop going out, with lenders re-investing the funds into new projects as they get loan payments back and new infrastructure activity attracting more interest from businesses and investors, Buendia said.

This jolt of activity also leaves ample room for people in historically disadvantaged communities to have their voices heard on how funds are spent, and also to forge their own careers in the budding green economy. Dream.org is among the organizations offering resources like scholarships and business development programs for people in underserved communities to transition their careers toward sustainability.

"This is a really big moment for people to see themselves as part of this future we're trying to build," Buendia concluded. "I would love to see a very, very strong economic message come out of this, where people really see this as a path of choice for them and for their careers. We need a full market transformation."

Mary has reported on sustainability and social impact for over a decade and now serves as executive editor of TriplePundit. She is also the general manager of TriplePundit's Brand Studio, which has worked with dozens of organizations on sustainability storytelling, and VP of content for TriplePundit's parent company 3BL.