PFAS are used as a coating on food packaging and are prevalent in other everyday items like personal care products and textiles.

Per- and polyfluorinated substances (PFAS) have been getting a lot of negative publicity. And with good reason. Classified as “forever chemicals,” they’ve been found in food, water, soil, animals and even our blood. Although the extent of their effects is not fully understood, they are known to negatively impact human health in a variety of ways. But while many are calling for an overall ban on the chemicals, pushback from the industry seeks to simply switch out the PFAS we already know are harmful with lesser-known ones that likely have the same — or possibly even worse — effects.

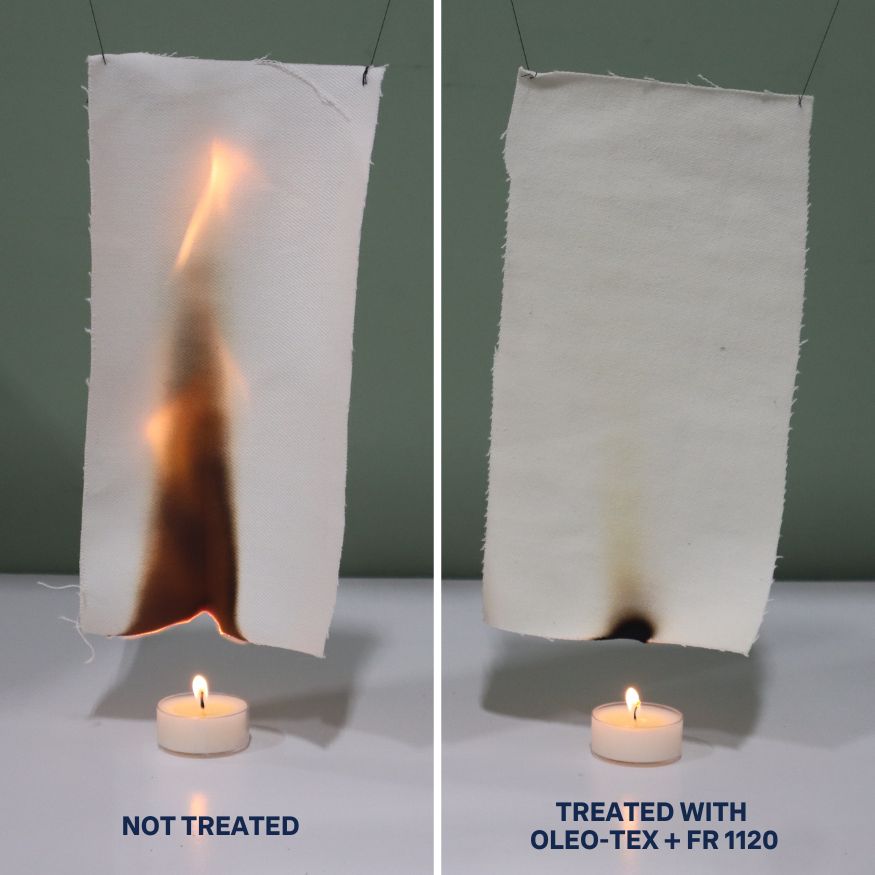

Although PFAS proponents argue that the chemicals are necessary for every aspect of modern life, innovators in chemistry are working hard to develop newer, safer compounds. Impermea Materials is one such company. Its water-based solutions can be used in place of PFAS in a variety of products — including packaging, apparel, upholstery, and technical textiles such as those worn by firefighters and military.

“We use different types of particles that are all inherently safe, they're amorphous,” David Zamarin, founder and CEO of Impermea Materials, told TriplePundit. “What we do is very different than the traditional chemical companies that are out there. We synthesize our own material and, by doing so, we can control a lot of the polymers and their functionality, which is very different because a lot of companies are just formulators.”

PFAS are everywhere

PFAS, or fluorinated chemicals, are ubiquitous in modern life. They are used in everyday items we all depend on, from cleaning and personal care products to non-stick cookware, touchscreens, batteries and fuel cells. They also appear in waterproof, flame-retardant and stain-resistant coatings on food packaging, upholsteries and textiles, among many more uses. As such, these chemicals have found their way into just about every part of our lives, down to the soil that grows our food, the water we drink, and sometimes even the air we breathe.

PFAS exposure is not equally distributed across the country. Those working in the industry’s manufacturing plants have the highest amounts of the forever chemicals in their blood, followed by people who live in areas with high levels of groundwater contamination, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But that doesn’t mean anyone is free and clear of the stuff — it’s in just about everyone’s blood in the U.S.

But what does that mean for our health? While not enough is known about the consequences of PFAS — especially at low levels — we do know that some levels of exposure increase the risk of various cancers, reproductive problems, developmental delays, compromised immunity, hormonal issues, obesity and elevated cholesterol.

Can alternative materials replace PFAS?

Some manufacturers argue that the most dangerous PFAS — those with smaller molecules — can be replaced by safer, larger-molecule versions. But a study out of Canada found that is simply not the case, at least when it comes to food packaging.

“As some legacy PFAS are withdrawn from the market or regulated, alternative compounds are introduced as replacements. The idea behind this process, sometimes called ‘whack-a-mole,’ is that the alternative is safer than the compound it replaces,” one of the study’s authors, Marta Venier, a professor at Indiana University, told the industry publication PackagingInsights. “In reality, the result is a regretful substitution since the newly introduced compound has similar properties to the compound it replaces. The replacement is considered ‘safer’ because less is known about that specific chemical.”

Instead of just switching out one type of PFAS for another, Impermea Materials has developed its own molecule — dubbed siloalkoxyurylsilane. “The molecule that we believe we've invented is a combination of a variety of different types of chemistry,” Zamarin said. “A lot of it is bio-based. There are reactive chemistries, resin technology, urethane technology and, of course, silica and some silanes. So it's a combination of a few things. And we make it in a very unique way, which is what allows us to combine all of these chemistries together, which normally don't like to be together.”

Third-party testing is an important part of the process, especially with food packaging that has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as is consistent in-house quality assurance. “We regularly test for fluorine content in both our water and then our finished goods,” he said. “We test for a variety of other chemicals as well in the entire gambit of PFAS. From a third-party perspective, we try to get any of our claims that we make like non-toxicity or PFAS-free tested independently.”

Understanding how PFAS replacements work

Impermea Materials works with producers to provide coatings for a variety of products. But not all of them have a thorough understanding of how to properly cure the chemicals after application, which has led to some using the same process as they would with PFAS.

“We have a lot of clients that are used to applying the traditional C6 based fluorochemicals, and they're used to curing it at 170 degrees Celsius, for example,” Zamarin said. “Well, if you cure ours at 170 degrees Celsius for the same amount of time, you're actually going to burn the coating. If you put it under a microscope, you'll see literal blisters, so you want to avoid doing that.”

Other clients have tried to bypass the curing process and allow the coating to air-dry instead. “It does air dry, it dries within a minute,” he said. “But you do need to heat cure it because the chemistry specifically has what's called crosslinking mechanisms. Heat specifically activates certain molecules to bond together and get to that performance."

Unlike PFAS, which can take thousands of years to degrade, Impermea Materials' coatings are compostable. As such, they also offer potential to address packaging waste — if they're used on a compostable package, of course, which is by no means a given. Even then, it's often hard to tell if a piece of packaging can really break down in a home compost pile or if it's only suited for industrial-scale composting, which is not available in most of the U.S.

“As of now, they have not been tested for home composability. That's what we mean is they’re industrially compostable," Zamarin said. "But the caveat here is we're not saying that it isn't home compostable. We just haven't done the testing."

“Generally speaking, it's the substrate that matters more than the coating," he explained. "That's a general statement. It's not entirely true with all of our competitors, unfortunately, but with our coatings, we don't impact the sustainability metrics of the substrate. So, if the food packaging itself is home compostable, it hasn't been tested yet, but we would assume from a technical background that it would also be home compostable for the coating.”

Chemicals and protective coatings are an invaluable part of modern life. However, as we become more aware of the consequences surrounding a variety of chemicals, the hunt for safer alternatives cannot be underestimated. Impermea Materials is one company that is working hard to find a solution, with applications in food packaging and textiles already in use.

Image credits: Kampus Production/Pexels and Impermea Materials

Riya Anne Polcastro is an author, photographer and adventurer based out of Baja California Sur, México. She enjoys writing just about anything, from gritty fiction to business and environmental issues. She is especially interested in how sustainability can be harnessed to encourage economic and environmental equity between the Global South and North. One day she hopes to travel the world with nothing but a backpack and her trusty laptop.