A sea turtle swims along the Great Barrier Reef near Lady Musgrave Island. (Image courtesy of Tourism Tropical North Queensland.)

The Great Barrier Reef is a UNESCO World Heritage site with some of the most spectacular scenery on Earth. It’s home to an eye-boggling array of marine life, including 400 kinds of coral, 1,500 species of tropical fish, and a variety of dolphins, birds and sea turtles. As the planet’s largest coral reef system, it’s the only living thing visible from space. It contributes billions of dollars to the Australian economy, protects the coastline, and holds cultural significance for First Nations peoples.

Despite its tremendous value, the reef is under threat from climate change, pollution, coral bleaching, coastal development, and outbreaks of coral-eating crown-of-thorns starfish. But now, it’s in the spotlight for a different reason entirely: an accolade.

The reef was nominated for a Champions of the Earth Award, presented by the United Nations Environment Program. This lifetime achievement award honors individuals and organizations working on sustainable solutions for climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution and waste. Previous recipients include naturalist David Attenborough, politician and environmentalist Al Gore and the National Geographic Society. The reef is the first non-human recipient to be proposed, thanks to the Reef Guardian Councils, Tourism Tropical North Queensland, and local communities and industries.

The motivation for this underwater nomination is to raise awareness of the reef’s status and spur support for reef conservation efforts worldwide. While an unconventional approach, it’s putting the reef back on our radars with a splash of positivity versus pessimism.

Why the Great Barrier Reef?

The Great Barrier Reef, the world's largest living structure, spans 1,430 miles and consists of thousands of individual reefs. Despite this impressive extent, it’s still interconnected.

“It moves and acts as one in so many ways,” said Mark Olsen, CEO of the regional tourism organization Tourism Tropical North Queensland. “When the United Nations Environment Program put out their lifetime achievement award, we thought, ‘It's for living individuals, so it's the world's largest living entity. Why don't we put an ecosystem forward?’”

Highlighting the Great Barrier Reef and its future — even while under threat — was one reason for the move.

“I think a lot of people see negative press around climate change and coral bleaching,” Olsen said. “There seems to be a growing global trend of a thought that there is an end for the Great Barrier Reef. So, we wanted to put that conversation back on track to remind people that it is the world's largest living entity. It's the world's youngest reef. It's only 9,000 years old, but its predecessors, its ancestors, go back millions of years, and they've adapted to enormous climate changes.”

Corals under climate change

Despite the resilient history of the reef, management remains critical while it faces stressors like coral bleaching. During these events, corals expel their food- and color-providing algae, leaving them at risk of disease and starvation.

“Climate change and coral bleaching are probably your largest threats to coral reefs all around the world,” said Bekki Hull, a marine biologist at the Great Barrier Reef tour operator Great Adventures. “When we're talking about climate change, many different threats are involved with that. The main one would be your sea temperatures increasing, but it can be through increased storms, as well. Increased runoff, increased rainfall, changes to the amount of salinity in the water, changes to the pH, all these things can be a stress to coral.”

While coral bleaching can be triggered by marine heatwaves, changes in salinity and sedimentation from runoff can also trigger these events, Hull said. Yet even if bleaching occurs, there’s a glimmer of hope.

“Coral bleaching isn't a death sentence,” Hull said. “Corals can bleach, but they can also have a chance to recover. It's all about that stress response, and if it's prolonged exposure to that stress, whether it's high temperatures, lower salinity, changes to pH, that's when we can start to see corals die off. But if that stress response goes back to normal quite quickly, that's when corals have a chance to recover.”

Nonetheless, it appears that these events are becoming more frequent and severe under climate change.

Rescuing the reef

Fortunately, there are ways to help the reef recover. The Australian and Queensland Governments invested in multiple projects, including improving water quality, controlling crown-of-thorns starfish, restoring river and coastal habitat, and protecting threatened species. And some organizations, like the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, are working to grow and ultimately plant heat-tolerant corals.

More aid is coming from an unlikely source: visitors.

“Tourism plays a really important role in reef monitoring and reef conservation,” Olsen said. “If it wasn't for the 2 million visitors a year that have spread across the Great Barrier Reef in very small numbers in small areas, we wouldn't be able to do the monitoring work to understand what's going on.”

Eye on the Reef is a long-term monitoring and assessment program that allows anyone to contribute to its database with an app. Likewise, Citizens of the Great Barrier Reef conducts a reef census once a year, and people can chip in by logging on and filtering through images, Olsen said.

Tourism also generates funding through a mandatory fee. “Through the fee that people pay to go out to the reef, there's an environmental management charge which goes to the reef authority, and it helps manage the reef system as well,” Hull said.

Businesses in the industry are doing their part, too.

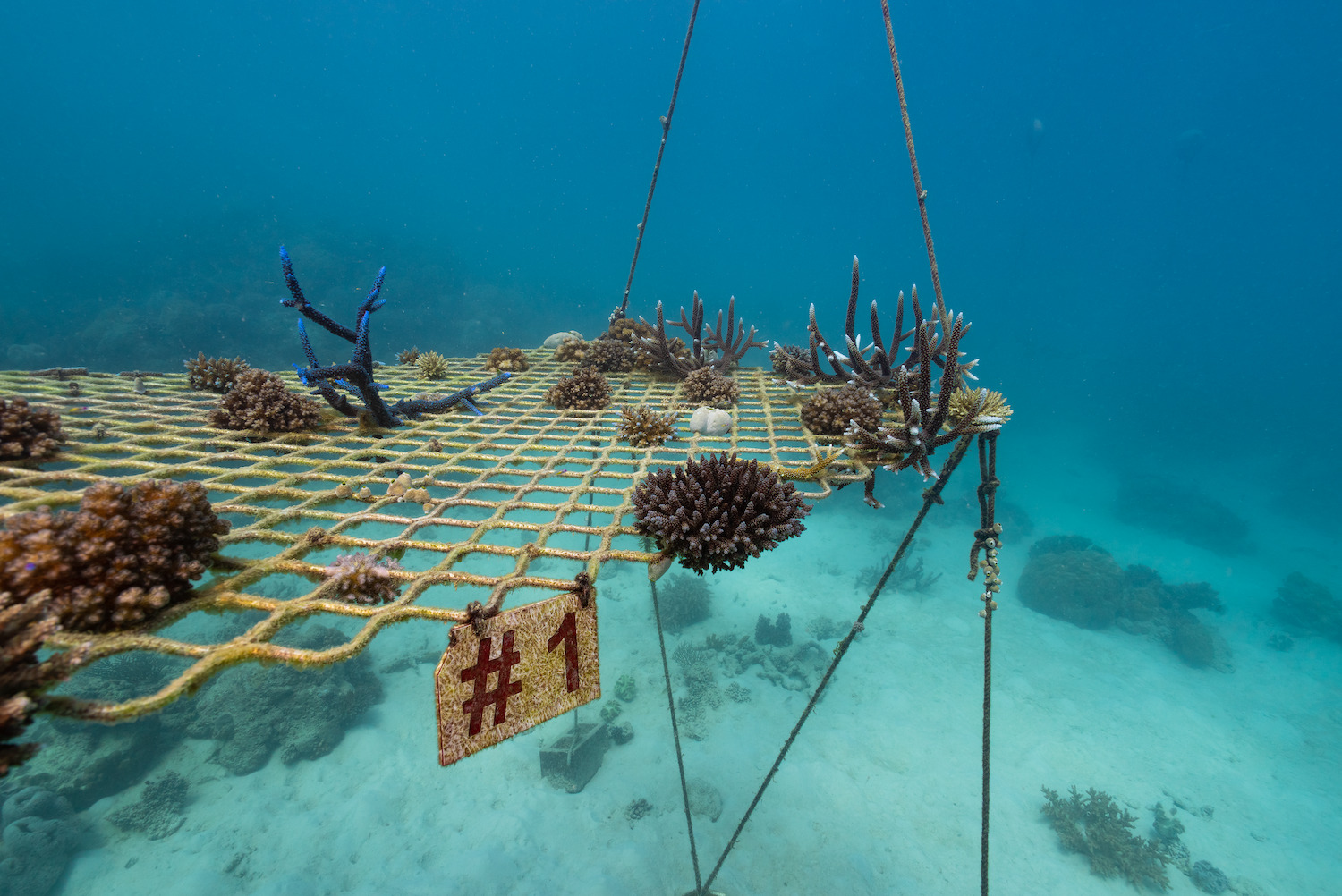

“We have an increasing number of tourism businesses that are involved in reef restoration programs,” Olsen said. “A broken fragment of coral can be replanted if it's picked up within a certain period of time. So we would never break coral off, but if you pick up a living piece of coral that's been broken off by, say, a cyclone and you reattach it to a firm structure, it will grow.”

In this process, organizations such as the Coral Nurture Program collect fragments, place them in a nursery, and eventually plant them back on the reef.

“A lot of these corals that do break off, they’re your branching corals,” Hull said. “That branch that falls off from the coral colony is going to grow back, but you're also growing a whole new colony.”

In fact, the Great Barrier Reef has the highest coral cover in the last 32 years of monitoring, predominantly due to the growth of the branching corals, Olsen said. These corals create structures for other species, such as soft corals, clams, sponges, crabs, sea stars and fish. While this increased cover points to the reef’s resilience, much of the growth comes from one family of corals, and a diversity of corals is still essential for the reef’s health.

While the Champions of the Earth Award won’t be announced until late 2025, the reef already stands out as the crown jewel of the Australian coast.

“We wanted to let the world know the reef is more than a beautiful picture,” Olsen said. “It's not a two-dimensional image. It's a living, breathing ecosystem. It's our friend, it's our teacher, it's our healer … So to recognize its lifetime contribution as important enough to be recognized with the award would be a bonus.”

Ruscena Wiederholt is a science writer based in South Florida with a background in biology and ecology. She regularly writes pieces on climate change, sustainability and the environment. When not glued to her laptop, she likes traveling, dancing and doing anything outdoors.