What’s so great about wilderness anyway? Does it even exist anymore? What does being “wild” even mean? Is nature just about ecosystem services, or is there an intrinsic value to the natural world beyond our interference, untrammeled by human activity?

There is no place on the globe untouched by the work of humanity, even where it is not the intent. From the highest mountain peak under a blanket of stars, a satellite will streak across the sky, carrying with it the incessant chatter of human civilization.

Evidence suggests a mindset of "taming” wilderness -- that the natural world is somehow ours -- has brought a kind of identity crisis for humanity in the 21st century. What does it mean to be human in an increasingly anthropomorphized world? How can modern civilization find its place in the scheme of things? Or to put it another way, how can the natural world find its place in the Anthropocene -- the “Age of Man?"

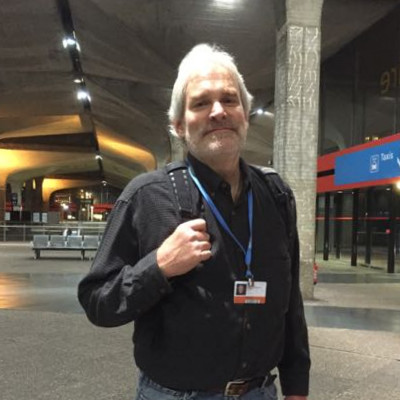

In his new book "Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man," author and environmental journalist Jason Mark explores the wilderness and questions what the very concepts of nature and wild mean for us today.

I had the opportunity to read an advance copy of Mark's book (which is now available) and chat with him about the state of the human-wild connection in the modern world. Building on the groundwork of Thoreau, Muir, Leopold and many others, Mark invites us on the ongoing journey of finding wilderness in the modern world.

Separation anxiety

Our attempt at bending the natural world to our will leads to separation, from the land and from ourselves. Evidence of this separation is found not only by the damage done within the biosphere, but also to ourselves, the human psyche. In our cleverness of survival from the primal reality of the wild, we've left behind a healthy relationship with nature.

For Mark, it is not an argument of a return to a “paleo state.” Even if we wanted to (or could) transform society into some paleo postmodern paradise, it would be impractical and as unsustainable as the current industrialized, connected and commodified world in which we live. Most of us would starve to death. There is no "going back."

But this, Mark contends, is why we need the wild now more than ever. “Wild” is a complex mental construct crossing generations, borders and beliefs. But it is also very real. "Satellites in the High Country" explores both. Mark describes in vivid detail the landscape of deserts, mountains, open plains and Arctic tundra, and the landscape of the conflicted human story of nature -- our halting efforts of preservation on the one hand with the ceaseless paving over of it on the other.

Mark journeys through wilderness that most of his readers will never see, and in doing so demonstrates why in just knowing there is wild, somewhere, we can remain grounded in our existence on the planet.

"So, even if you never go into wilderness," says Mark, "it's important psychologically to just know that it's there ... There's just this hunger that we have for someplace that's away."

Doing business in the Anthropocene

How does “enlightened capitalism” define the value of nature beyond ecosystem services? How do we reign in our desire to consume beyond need or well-being, not from force or coercion, but by cooperation? Mark doesn’t pretend to have the answers, but he eloquently brainstorms possibilities.

Referring to John De Graaf's work on alternative economic models outlined in the book "What's the Economy For Anyway?," Mark suggests metrics beyond simple GDP can help shift our view of perpetual economic growth in a world encroaching on its limits.

"Theoretically the economy should serve human progress, human well-being and human happiness," Mark says. "I think it's imperative that we move beyond GDP and pioneer new ways of measuring progress and well-being. When we get there, we'll begin to see a more scientific way of seeing that more stuff does not equal more happiness."

Refuge of the wild

Certainly in today’s world, it often looks as if we are sawing off the very limb of the tree of life upon which we precariously perch. Only by reconsidering our relationship to the world outside, through our personal choices, our civic cooperation and the businesses and economies we create, can we mend the wound we inflict upon ourselves and the planet.

"I'm cautiously optimistic," Mark says. "There's no question that the challenges facing us are immense, because of global population, because of consumption, and because of these cascading and mutually reinforcing environmental crises. That's worrisome. Let's not kid ourselves, we're in a tight place. That said, I am hopeful that people can continue the deep-seated and innate love of wild places."

If Mark romanticizes the refuge found in the wild, he makes no apologies for it. "Satellites in the High Country" is an evocative meditation on reconnecting our bond to the natural world, and why it is so important.

"Whether it is the deep wilderness or nearby nature close to home," say Mark, "that emotional connection will in the end spur a critical mass of people to demand a new way of meeting our basic needs and our appetites."

But Mark's is more than a romantic vision. It is also a pragmatic understanding that, to save ourselves, we'll need to reconcile our fractured relationship to the wild in the Age of Man.

Image credits: 1) Filckr/Rachel Kramer 2) Island Press

Tom is the founder, editor, and publisher of GlobalWarmingisReal.com and the TDS Environmental Media Network. He has been a contributor for Triple Pundit since 2007. Tom has also written for Slate, Earth911, the Pepsico Foundation, Cleantechnia, Planetsave, and many other sustainability-focused publications. He is a member of the Society of Environmental Journalists