Over the past few years, TriplePundit has reported on Ford Motor Co.’s use of bioplastics in its vehicles, both as a means of lightweighting certain components and as a way to reduce the fossil fuel content in vehicle parts.

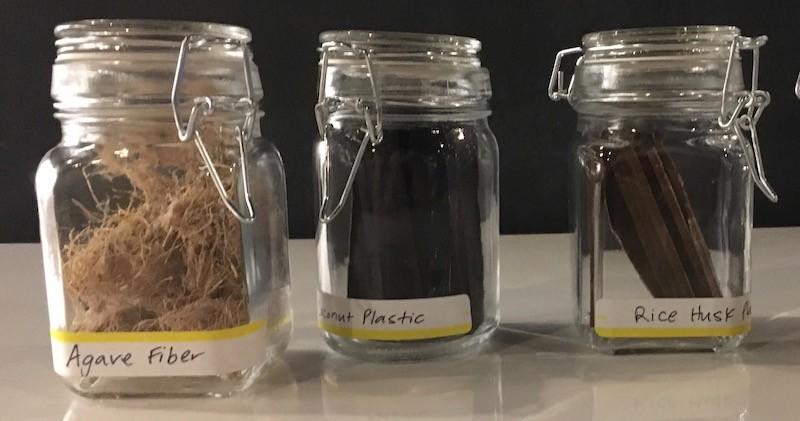

Earlier this summer, the company partnered with Jose Cuervo to test the use of agave fibers in certain components such as air conditioning systems and wiring harnesses. These fibers, a byproduct of tequila production, join the list of other natural materials Ford incorporates into various components in vehicles on sale today.

We caught up again with Debbie Mielewski, Ford’s senior technical leader of sustainable materials, to check in with the automaker’s ongoing efforts to continually evaluate new biomaterials, as well as understand a little bit more about how to select suitable materials for various components. Also, we were curious to understand the opportunities and challenges of recycling these components at the end of a vehicle’s life.

Mielewski said her team’s ongoing goal is to innovate "better utilization of things that other people call waste.” Meaning, for example, natural fibers recovered from agricultural byproducts can be manufactured into various vehicle components; some parts are as simple as cup holders, while others are semi-structural in nature. For any given application, the natural fiber components are only substituted in once they are tested to meet specifications for performance and durability for a specific application.

There are, of course, some technical hurdles when developing certain materials. For example, some natural fibers contain impurities, which cause odor and volatiles to emanate if they get too hot. This means some fibers, like agave, are better in “underhood” applications rather than for interior components. Conversely, Ford has been able to purify cellulose fibers from trees to remove “low molecular weight bodies,” allowing them to withstand higher temperatures.

In addition, Ford tries to select fibers proximal to specific manufacturing locations. For example, the company uses wheat straw from nine farms in Ontario, Canada, and incorporates this waste material into storage bins for the Ford Flex that’s assembled there. The work being done with agave fibers will be relevant to manufacturing in Mexico, where blue agave farming is big business.

Some of these fibers are selected as filler material to reduce the amount of fossil-fuel derived plastic used in certain components -- often making the parts lighter in weight, too. Other times, natural fibers are blended into parts to add strength. In either case, a component may be comprised of up to 30 percent natural fibers.

Furthermore, as well as saving fossil fuels by reducing the polymer content of a component, these fibers often replace traditional filler materials such as talc (which is very energy intensive to mine) or strengthening material such as glass fiber (which is very energy intensive to manufacture). So, as Mielewski explained, “In all cases, these materials are better for the planet.”

In many cases, the natural fibers blended into polymers perform better than the traditional materials they replace. For example, in traditional glass fiber, the glass fibers themselves are three millimeters in length in a virgin state. But after molding into a complex part, those fibers break and can end up as little as half a millimeter in length. In other words, material properties are degraded in the manufacturing process. On the other hand, natural fibers in polymers used for strengthening can initially be cut to variable lengths as appropriate for a given application, and those fibers have been found to suffer no degradation even after remolding a component up to five times.

This attribute holds potential not only for strength, but also for recyclability at the end of a vehicle’s life. Whereas glass fiber has to be downcycled, maybe these natural fiber infused polymers could be more valuable for reuse?

Unfortunately though, despite the fact that these materials are recyclable, no recycling streams have been established as of yet. That's because the economics are not great at the moment.

With current oil prices being so low, Mielewski says virgin plastic works out cheaper. Furthermore, even if oil prices rise and recycling gains an advantage, recyclers will still have to work out how to efficiently detach the plastics from vehicle parts which tend to be comprised of mixed materials. Think about a car seat -- which has a structural base, a foam cushion and cover material. So, unfortunately, Mielewski explains, “You’ll have to have reasonably high oil prices and plastic prices to get people motivated in these technical areas.” Perhaps we can hope that by the time a car built today reaches end-of-life in 10-plus years, progress has been made in this area.

Despite limited recycling opportunities at the moment, fortunately, the use of natural fibers in plastic components do remain economically viable in Ford’s vehicles today, even with protracted low oil prices. That’s in part because Ford got a head start in developing these materials back in 2001 during another period when oil was cheap and the economics were not conducive. By going through the development cycle when oil was cheap, it meant that when oil prices spiked later in the decade, they had production-ready soy-based foams ready to roll out; a material which was more sustainable and had suddenly become cost effective.

Since then, Mielewski said Ford, “has established a corporate philosophy; that we must use sustainable materials when they meet performance requirements and they are affordable.”

Image courtesy of the author

Phil Covington holds an MBA in Sustainable Management from Presidio Graduate School. In the past, he spent 16 years in the freight transportation and logistics industry. Today, Phil's writing focuses on transportation, forestry, technology and matters of sustainability in business.