President-elect Donald Trump ran his campaign on the unlikely promise of bringing coal jobs back to the U.S. Fulfilling that promise is growing unlikelier by the day.

In the latest development, a multinational research team has unlocked one of the mysteries behind plants' natural ability to "split" water. The discovery provides foundational support for efforts to produce renewable hydrogen fuel with low cost, high efficiency water-splitting systems.

Renewable hydrogen from water

The march toward renewable hydrogen is progressing along several different fronts, aided by solar power as well as biomass, wind power and tidal power. That technology is already beginning to ease into the marketplace.

In Europe, for example, rail transport company Alstom introduced a fuel cell train that appears to leverage a recently formed relationship with the sustainable hydrogen company Hydrogenics.

Fuel cell electric vehicles have been slow to hit the open road here in the U.S. But hydrogen fuel cells are rumbling into niche markets, such as in the logistics industry and seaports.

This growing market makes it imperative to transition out of the primary source for hydrogen -- natural gas -- and into more sustainable alternatives.

The new breakthrough could help accelerate that trend by providing a helpful course-correction for renewable hydrogen research.

The Energy Department's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory spearheaded the project. It provides the first atomic-scale visualization of the protein complex that plants deploy during photosynthesis.

Named photsystem II, this protein is the nexus where energy from sunlight splits water to create oxygen along with protons and electrons -- useful bits of energy that are later used to transform carbon dioxide into solid plant material.

How important is this breakthrough? Co-principal investigator Vittal Yachandra offers this take:

“We have been trying for decades to understand how plants split water into oxygen, protons and electrons. Understanding how nature accomplishes this difficult reaction so easily is important for developing a cost-effective method for solar-based water-splitting, which is essential for artificial photosynthesis and renewable energy.”

Yachandra further explains that the new imagery may lead to the adjustment of some important assumptions researchers previously made about natural water-splitting. Until now, the leading theories indicated that water binds to specific sites in the photosystem II protein. That phenomenon was not revealed by the imagery.

Next steps for the team include deploying the process of elimination to gain a more accurate understanding of the actual mechanism at play.

Group hug for U.S. taxpayers

Eliminating the Department of Energy has become a favorite theme of Republican office-seekers. The theory seems to be that the private sector will pick up where taxpayer-funded projects leave off.

That may be true in some areas of research, but when you get down to the primary or financial level, market incentives practically evaporate. For example, the Internet as we know it today is the product of a Defense Department research program, for which each taxpaying member of the public can claim some credit. That kind of high-risk, high-reward investment requires a measure of time, human resources and dollars that are difficult if not impossible to assemble in the private sector.

The new Berkeley project is a good example: The team deployed publicly-owned equipment to create the new image.

"The images ... provide the first high-resolution 3-D view of photosystem II in action, a feat accomplished by using unimaginably fast X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) pulses from the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, a DOE Office of Science User Facility."

Got all that? Located at Stanford University, SLAC National Accelerator was credited with an Encyclopedia Brittanica's worth of discoveries since it launched operations in the 1960s.

In short, LCLS does this:

"With X-ray pulses a billion times brighter than predecessor X-ray sources that last for just femtoseconds, or million-billionths of a second, LCLS can measure the properties ultrafast processes at the scale of atoms and molecules."

This is only one of two facilities in the world where this kind of operation is possible, btw.

Another angle that would be difficult to engineer on private-sector dollars alone is the international cooperation that takes place at the level of foundational research. The Berkeley research team included representatives from Germany's Humboldt University, Sweden's Uppsala University and England's Oxford University, as well as compatriots from Stanford University and the Brookhaven National Laboratory.

If President-elect Trump can use his powers of persuasion to get private dollars to fill in for this kind of operation, good luck.

Meanwhile, another XFEL is up and running in Europe, so at least hydrogen stakeholders have another place to go if Trump decides to pull the rug out from under hydrogen research in the U.S.

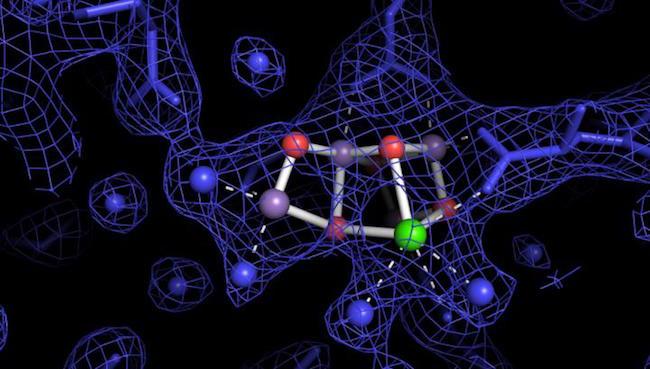

Image: by Johannes Mssinger via Eurekalert.org, "...structure of the oxygen evolving complex in photosystem II in a light-activated state. Water molecules are shown as blue spheres, the four manganese ions in purple, the calcium ion in green and the bridging oxygen ions in red. The blue mesh is the experimental electron density, and the blue sticks are the protein side chains holding the catalytic complex."

Tina writes frequently for TriplePundit and other websites, with a focus on military, government and corporate sustainability, clean tech research and emerging energy technologies. She is a former Deputy Director of Public Affairs of the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, and author of books and articles on recycling and other conservation themes.