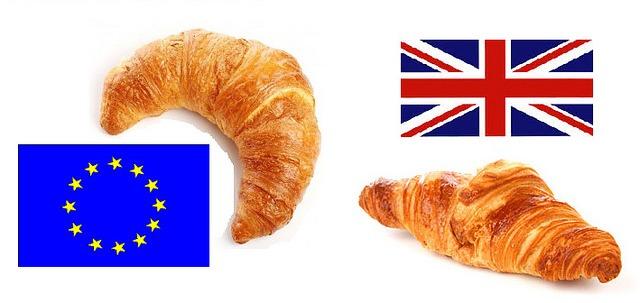

International trade deals are never easy. Still, figuring out who is on first and second base post-Brexit adds a whole new dimension to bilateral trade negotiations.

First there was the European Union and U.S. trade deal, less affectionately known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, an ambitious if not controversial concept that included trade advantages with the United Kingdom. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, American exports to the British Isles are notable. In 2015, the U.S. exported more than $56 billion in goods to the U.K. Britain did even better: It imported more than $57 billion to the U.S. that same year. And that’s without the sweeping provisions of the prospective TTIP in force.

But that was also before Britons voted to leave the EU in June. Few believed the Brexit camp would actually succeed, including its organizer, former London Mayor Boris Johnson.

Still, U.S. President Barack Obama concretely spelled out the implications of Brexit -- and the U.S. losing the U.K. as a cross-table negotiating partner at the TTIP -- a few months before the June 23 vote, when he told Britons what could happen if Brexit went through.

“The U.K. is going to be in the back of the queue.” Obama was referring to the U.K.'s prospects of striking a new trade deal with its American business partner. It's not that trade with the U.K. doesn't matter to U.S. interests. But “negotiating with a big bloc,” like the EU, was in its interests as well, Obama said.

But of course, that was pre-Brexit. And it was also before the U.S. found that concluding the TTIP with the Europeans was going to be much harder than expected.

European negotiators accuse the U.S. of being unwilling to negotiate on terms, including workers’ rights and the ability for EU member states to bid on contracts. A clear, balanced negotiation toward those two issues is a sticking point for European member states.

It's also apparently an issue of contention for the U.S. team.

“That’s no basis for negotiations,” Bernd Lange, the EU’s chief negotiator, complained in reference to America's perceived unwillingness to talk about labor standards and public procurement of contracts. “Internally we’ve said we’re going to give it a chance until July, but I can’t imagine the U.S. will have a big change of heart. I’m expecting this won’t work out.”

And that’s where the U.S.-U.K.’s hopeful new trade deal comes in.

Last week, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and the U.K.’s brand-new foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, joined forces at a press conference in London to discuss a new plan to push a trade agreement with the U.K. back up to the front of the queue. Both Kerry and Johnson acknowledged that, while a firm deal between the two nations can't proceed until the U.K. has actually left the EU, there was nothing preventing the two countries from hammering out the deal together, the Guardian reported last week.

"[Clearly] you can begin to pencil things in, you can’t ink them in,” Johnson summarized.

Well, that was last week's understanding, apparently. This week, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, French President Francois Hollande and the U.K.'s new Prime Minister Theresa May re-discussed the terms that prompted the Brexit vote to go through in the first place: Europe's Freedom of Movement rules.

Under the terms of EU membership, workers have the right to freedom of movement throughout EU member states. It's a contentious issue in northern England, and has been a sticking point to continuing EU membership in the past.

But this week, EU representatives spoke candidly of loosening those rules for Britain, if it would stay in the EU. The price would be stiff, however: In return for an "emergency brake" on EU migration for seven years, the U.K. would forfeit some of its voting rights.

As for a U.S.-U.K. trade deal, however, all bets are off until the EU and Britain (which is still formally part of the EU) have clarified their relationship. That leaves the Obama administration not only without added leverage at the EU bargaining table, but without a clear path to a U.K. business deal. But knowing that the country it refers to as "no closer ally" will remain at the the TTIP bargaining table may make the wait all the easier for the next round of U.S. negotiators.

That is, of course, unless Donald Trump has a say in the matter as the next president ...

Images: Flickr/Sam; Flickr/Mike Licht

Jan Lee is a former news editor and award-winning editorial writer whose non-fiction and fiction have been published in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, the U.K. and Australia. Her articles and posts can be found on TriplePundit, JustMeans, and her blog, The Multicultural Jew, as well as other publications. She currently splits her residence between the city of Vancouver, British Columbia and the rural farmlands of Idaho.