An environmentalist and a Republican walk into a bar...

The punch line is that the Republican and environmentalist are the same guy. Though it needn’t be a “punch line” at all.

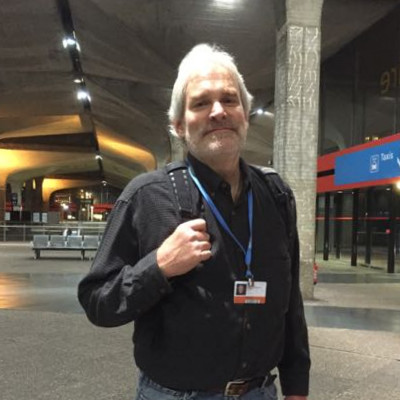

Jim Brainard, mayor of Carmel, Indiana, reminds as many as will listen -- Democrat, Republican or “none of the above,” but especially his GOP colleagues -- that it wasn’t always like this.

“I like to try to look at it from a historical context,” Brainard told TriplePundit by telephone from his office shortly before leaving for the GOP convention earlier this month. “It was Teddy Roosevelt that set aside most of the national parkland. It was Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican, who set aside the Arctic Reserve. It was Dick Nixon who signed legislation for the EPA, the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the [amended] Migratory Bird Act … our entire federal environmental regulatory system [was formed] under Nixon.”

Even Reagan himself had sympathy with environmental causes.

“[Reagan] believed the scientists who spent their lives studying these issues, went to Montreal and signed the Montreal Protocol to deal with the ozone hole,” Brainard said.

Wait, Reagan?

Reagan certainly did right on behalf of the global community when he signed the Montreal Protocol. But it’s also fair to say that the Reagan administration had an uneasy relationship with domestic environmental protection. During Reagan’s tenure, my father worked under Secretary of Interior James Watt, infamous for his disdain of conservation, environmentalists and liberals.

As chief of the biological services branch for the Office of Surface Mining, my father’s division was responsible for overseeing mine reclamation throughout the American West. Watt wanted none of it.

“Watt made our life miserable when I worked at OSM,” my father recently told me:

“He wanted to do away with us and tried to close our Denver office. It was miserable working for OSM then. It got so bad [that] everybody was desperately sending applications and trying to leave before Watt managed to get rid of us. But things did eventually stabilize. Watt had to be the worst Interior Secretary ever…” (Though Albert Fall, made infamous by his involvement in the 1922 Teapot Dome scandal, is arguably a strong contender.)

Watt’s intransigence for environmental law and conservation hints at an assumed narrative among many conservatives toward conservation that is often characterized as “environmental fascism.” Watt notoriously suggested that his critics had a “larger objective” of central control similar to the German Nazis and Russian Bolsheviks.

Such utterances from Watt proved a political liability for Reagan, eventually leading to his dismissal as Interior Secretary. Watt still managed to quintuple the amount of federal land leased to coal mining operations. He clearly valued unchecked development over preservation, conservation or reclamation.

For Brainard, this isn't being a true conservative at all.

Not your father's conservative party

Does Watt's partisan extremism represent a fracture in the conservative tradition? Maybe so, at least the tradition of conservation of which Brainard speaks. “Traditionally, these issues have been more or less non-partisan,” Brainard told us.

Take, for example, the Land and Water Conservation Fund. The LWCF provides for parks, wildlife refuges and historical cultural sites with money raised from offshore oil and gas development on the outer continental shelf. “That was done by unanimous voice vote in the House when it was first passed 51 years ago,” Brainard said.

If the creation of the LWCF demonstrates the promise of environmental non-partisanship, its subsequent implementation reveals a more troubled narrative, one that dogs the GOP to this day. Beleaguered by consistent underfunding, the LWCF has died a thousand deaths since its passage.

Congress denied permanent reauthorization of the fund last September. Temporary reauthorization was granted in December. The Energy Policy Modernization Act of 2016 seeks to make that permanent, but even with support from some Congressional Republicans, its future remains uncertain.

Despite the non-partisan impulse of their predecessors in Washington, conservation, environmental protection and sound energy policy struggle to find common ground in Congress. Mayor Brainard insists it doesn’t have to be this way.

“Quite honestly, if you’re conservative, but have questions about the science, wouldn’t you err on the conservative side, that there is a problem, as opposed to the more reckless -- you could say, liberal -- position and say, 'No, it’s not a problem. I don’t believe the scientists,’” Brainard asked rhetorically.

The view from the back porch

A popular six-term mayor, Brainard was awarded the Bicentennial Green Legacy Community Award for spearheading numerous initiatives,including energy efficiency and alternate-fuel city vehicles, a curbside recycling program, promoting mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly development, expansion of public green space, and implementation of roundabouts throughout the city to ease congestion and reduce pollution.

"... Carmel, through the mayor's leadership and community engagement, has distinguished itself as being a model of sustainability and is on a path that is exemplary,” John Gibson, state coordinator for Sustainable Indiana 2016, said in a press briefing.

“I think there are a lot of Republicans that do care about the environment. Certainly the environment in their cities,” said Brainard, referring to an old saying that “everybody looks at their city from the back porch.” Indeed, the nexus of change happens at the city level, where people live. “I have yet to meet a Republican, or a Democrat, that want to drink dirty water or breathe dirty air."

“There’s no ‘Republican’ way and no ‘Democratic’ way to move snow, fill potholes, run the fire department -- mayors are about providing services and a high quality of life to their constituents,” Brainard said. People living in cities “are concerned about climate."

As a trustee of the U.S. Conference of Mayors and co-chair of the Energy Independence and Climate Change Task Force, Brainard regularly takes his message to Washington. “Ninety-nine percent of the mayors in the country, at least one-third of whom are Republicans, signed, in essence, the Kyoto Protocol,” said Brainard, pledging voluntary targets to reduce emissions in their cities.

“I wish the Republicans in Washington got out more and talked to their average constituents more about what really concerns them,” Brainard said, “because I think there’d be a sea-shift of change if they would.”

BP: Beyond partisanship

Politics is, after all, about the art of the possible, not about “us” versus “them.” Or at least it should be.

“I’m so tired of party labels,” Brainard said. "[Conservation] should be a non-partisan issue."

“Our nation’s discussion should be about ideas, economic opportunity, and how it makes life in the United States better … and Americans safer. Not about party politics," Brainard says. "I'm very concerned that the debate has become so one-sided that people serving in Washington, in one party or the other, are literally told how to think about issues. That’s why I talk to the media and try to make an effort about it. Hopefully, if I do it, other Republicans that feel the same way but kept it quiet may start speaking out about it.”

Whether that will happen in the current divisive, circus-like atmosphere of American politics remains to be seen. If Brainard's outlook on environmental issues appears to rub against the grain of the Republican party in Washington, it doesn't seem to bother his constituents.

Adam Rome, writing in Discourse in Progress, echoes the historic conservative tradition of conservation:

"In October 1969," Rowe wrote, "six months before the first Earth Day, columnist James Kilpatrick challenged fellow conservatives to help solve the nation’s environmental problems. He feared that the Right would make little headway unless it overcame its image as 'the negative party,' and he argued that the issues of pollution and sprawl and DDT poisoning of the environment provided perfect opportunities to 'translate broad conservative principles' into 'affirmative actions.' The degradation of the environment, he concluded, was essentially 'a problem of conservation — of conserving some of the greatest values of America; and conservatives, of all people, ought to be in the vanguard of the fight.'”

We’ll all just have to hold our noses, move to common ground, and work together to figure these challenges out. They aren’t going away nor will they ever be solved through political posturing.

Circling back to our opening one-liner: a Republican and an environmentalist walk into a bar. It's no joke.

They sit down over a beer and consider how they can make their communities better for all their neighbors. Is that such a radical idea?

Remember Teddy Roosevelt.

This post is dedicated to my Father, who spent a career in public service and environmental stewardship. Through Republican and Democratic administrations, Dad stayed true to his calling -- to make a good life for his family and a better world for all. Thanks, Dad!

Image credit: Jenni Konrad under creative commons license, courtesy Flickr

Tom is the founder, editor, and publisher of GlobalWarmingisReal.com and the TDS Environmental Media Network. He has been a contributor for Triple Pundit since 2007. Tom has also written for Slate, Earth911, the Pepsico Foundation, Cleantechnia, Planetsave, and many other sustainability-focused publications. He is a member of the Society of Environmental Journalists