Refugees seeking salvation from their war-torn countries are often met with harsh realities in their new homes. Beyond finding ways to educate their children, support their families and avoid prejudice, many refugees lack proper identification -- which can complicate their efforts to open a bank account.

Meet Taqanu, a new startup aiming to help refugees assimilate to their new countries by giving them an alternative way to prove their identity. The “bank for all” company allows people to use their smartphones — a popular commodity among refugees — to create a digital profile. The app compiles data including social media information as well a “reputation network,” which lets friends and family members confirm the user’s identity. The more the app is used, the more data it collects to improve the user’s profile.

This identity-building app would allow banks to trust the identity of the refugee and thus open an account in his or her name. Without access to a bank account, refugees cannot deposit checks or safeguard wages earned from work. This, as senior director for economic recovery and development at the International Rescue Committee, Radha Rajkotia, told Fast Company, can push refugees toward an informal economy.

“If you don’t actually have an account to be paid wages, it keeps people working in the black [market] economy,” Rajkotia said.

Without a stream of income, refugees can choose to partake in underground economic activities.

Newsweek reported in May 2016 that as many as 18,000 Syrians had sold their organs on the black market in order to fund their trips out of Syria since the start of the conflict in 2011. And ABC reported in January that Egypt and Turkey, two popular destinations for Syrian escapees, have become “epicenters for organ trafficking.”

A 2015 Vice article highlights the impossible choice Syrian refugees face in Jordanian camps: Stay in the camp, or work in the black market. Stores are willing to take chances on Syrian refugees because the reward -- paying Syrians half as much to work twice as long -- heavily outweighs the risk of getting handed a small fine or court notice.

This informal economy also intensifies relations between the refugees and the citizens in their new homes. Citizens hosting the refugees sometimes view them as stealing work from their own countrymen and avoiding paying taxes because of the under-the-table standard.

If Taqana is able to secure partnerships with banks and properly advertise its service to refugees, the app could potentially push refugees to the formal market and allow them to reap major benefits. But it’s still an uphill battle for Taqanu.

The company needs to overcome regulatory approval and slow bureaucratic agencies; it must gain bank cooperation and funding. It’s also quite possible that refugees simply may not want the service because they don’t want to be tracked. If the refugees plan on hopping borders and moving country to country until they feel comfortable, they will likely be hesitant to use a service that wants to track their every move.

Daniel Buchner, head of decentralized identity at Microsoft, the computer giant helping advise Taqanu, said the biggest challenge the app faces is regulation.

“I’d say their No. 1 challenge is governments and bureaucratic agencies being slow to adapt their models and regulations to enable new types of innovation that may not fit within the confines of rules that create a slew of unintended consequences,” he told Fast Company’s Adele Peters.

Taqanu seems to have the best chance at early success in Germany. In 2016, Germany enacted a law requiring banks to offer at least basic services to everyone, including refugees. However, banks have been slow to fully adopt the law, mainly because questions remain over identification and the potential for money laundering. Taqanu’s model for providing transparency and identification to refugees may very well help ease those hesitations for banks.

The company is slated to present its app to bankers and policymakers at the G20 summit in Hamburg, Germany, this summer.

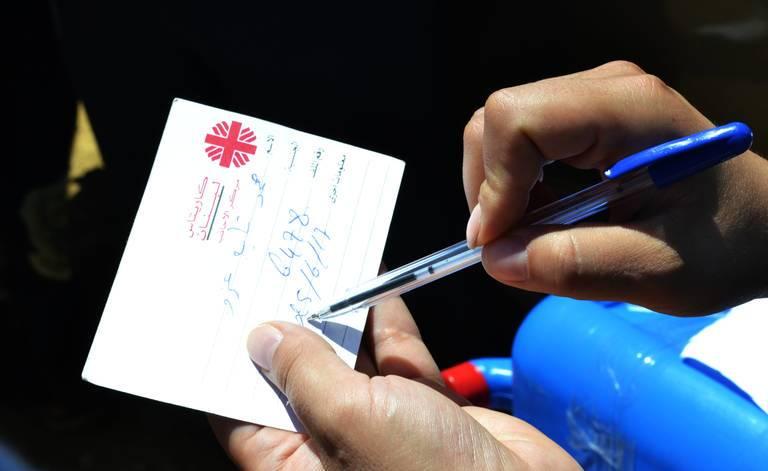

Image credit: Trocaire/Flickr

Based in Atlanta, GA, Grant is a nonprofit professional and freelance writer passionate about affordable housing and finding sustainable approaches to international development. A proud graduate of the University of Maryland, Grant spent four months post-grad living in Armenia where he worked for Habitat for Humanity and the World Food Programme. He enjoys playing trivia with friends but is still seeking his first victory - he ceaselessly blames his friends lack of preparation.