Critics often argue that because electric vehicles are often powered by electricity produced at coal-fired power plants and other fossil fuel facilities, they aren’t necessarily any cleaner than gasoline-powered cars. Their logic is that while all-electric cars do not emit carbon dioxide from the tailpipe, they are still responsible for significant emissions during recharging.

On a recent China Global Television Network episode of “The Heat,” panelist Tu Le, managing director of the strategic advisory Sino Auto Insights, agreed with that logic, to a point. In the short term, Le said, the arguments that EVs produce their own form of emissions may be true. However, he—like many others before him—predicted that carbon emissions resulting from electricity production will decline in the future. “In the next 15 to 20 years, as energy storage becomes more mainstream, and solar and alternative forms of energy become mainstream, that [criticism] becomes less relevant,” he explained.

Other analysts, including Jeremy Hodges of Bloomberg, have made the case that EVs still run cleaner than gasoline- or diesel-powered vehicles in the long run, even when they're directly powered by a coal-fired power plant.

The EV critics’ double standard

Further, the characterization that EVs alone are responsible for heavy emissions during recharging is not an accurate critique, some experts say.

David Reichmuth, a senior vehicles engineer with the Union of Concerned Scientists, points out the double standard sometimes applied to evaluating emissions from fuel production. Gasoline-powered vehicles, too, can’t just be assessed at the tailpipe. Vehicles with conventional internal combustion engines (ICEs) are also responsible for emissions during crude oil extraction, the refinery process and their transportation to filling stations.

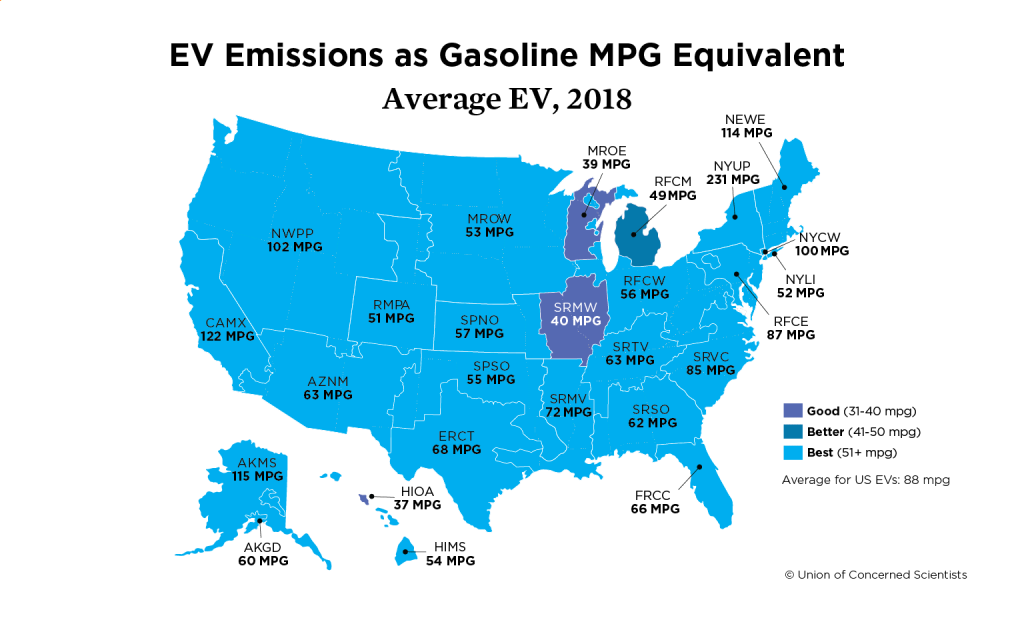

When assessing the true emissions of each vehicle type in a state-by-state study, Reichmuth found that driving the most inefficient EV still resulted in fewer emissions than any gasoline car on the market, in almost every state. In upstate New York, for example, the difference was extreme: Electric vehicles produced one-tenth of an average ICE vehicle’s emissions.

Image courtesy UCS

As the map above shows, your average, run-of-the-mill electric vehicle beats out a gasoline-powered car in nearly every state when it comes to fuel efficiency. Only parts of Minnesota, Illinois and Missouri were able to deliver fuel to gas-powered vehicles efficiently enough for ICE cars to match the 39 to 40 MPG equivalent of EVs.

EV efficiencies are just warming up

As Le pointed out in his segment on “The Heat,” electric vehicles are only going to become more energy efficient in the future.

Reichmuth’s UCS report highlighted a number of factors driving this rise in efficiency. From 2018 to 2019, the proportion of Americans living in a region where EVs can unlock greater than 50 MPG fuel efficiency surged from 45 percent to 94 percent. Similarly, as of 2018, EVs emit less than conventional 50 MPG vehicles in 22 of the 26 major electricity grid regions in the U.S., up from nine in 2009.

Meanwhile, electricity sources throughout the U.S. are trending toward lower emissions: From 2009 to 2018, the use of coal for energy declined sharply, from 45 percent of the U.S. energy mix to 28 percent. Meanwhile, the total amount of power sourced from solar and wind power technologies rose from 2 percent to 8 percent.

Can we have our SUVs and electric vehicles, too?

SUVs have long been the subject of criticism for their fuel inefficiency and contribution to emissions, but do they need to go down in history strictly as gasoline hogs and emissions chart toppers? Not necessarily. After all, larger EVs are already hitting the market.

While these larger EVs are less efficient, they only emit 25 percent to 50 percent of the carbon dioxide their gasoline-powered peers do, Reichmuth found.

Meanwhile, based on regional supply chains, the most inefficient all-electric SUV, the Audi e-tron EV SUV, performed much better than the automaker’s ICE version. After crunching the numbers, Reichmuth found that when comparing Audi’s gasoline SUV to the all-electric model, the EV halved emissions for 8 percent of the U.S. population. Almost three-quarters of the population would see emissions savings from 50 percent to 75 percent by swapping their Audi SUV for an all-electric model, and nearly a fifth would realize savings in excess of 75 percent.

While not every American can afford an Audi SUV, whether it is gasoline-powered or all-electric, the data nonetheless presents a clear picture of reality, both today and in the future: Switching to electric vehicles results in lower carbon dioxide emissions. Watch for the performance of these vehicles to improve as automakers, from GM to Volkswagen, roll out new all-electric models and introduce new technological innovations. Those emissions savings will only become more efficient as time goes on.

Image credit: Audi

Greg Heilers writes on green business and sustainability for private clients and top publications. After graduating from university, he had the privilege to learn from opportunities in France, Palestine, Scotland, Guatemala and the USA. Today, he lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, and enjoys any chance he gets to garden or hike.