2020’s arrival started a ticking clock on our most urgent global development goals—most notably, the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While the New Year saw commentary flood the mainstream media with calls for much-needed action on climate change, on another crucial issue with an associated SDG—striving for no poverty by 2030—there has been little discussion.

The prospects for no poverty by 2030 seem daunting: According to UN's Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, the world is largely off-track to achieve the SDGs within the time frame. If we fail, it won’t be because we lack the tools, or even the money, although the distribution of the latter leaves the outcome in serious doubt. But make no mistake: SDG #1, No Poverty, is achievable, and if we act swiftly and collectively, we can get there.

Yes, we can achieve SDGs, including no poverty by 2030 - here's how

After decades at the forefront of developing market-based solutions to global poverty, I have seen firsthand the impact that integrated action can have on poverty alleviation. But we’ll only succeed with meaningful investment (and I don’t just mean financial) from businesses, policymakers, heads of state, faith-based organizations, multilateral development organizations, and NGOs. With this in mind, here are the urgent steps we must take to achieve SDG #1 in this decade.

First, the private sector must invest—big. A troubling 10 percent of the global population (roughly 736 million people) still lives in extreme poverty, according to the most recent World Bank estimate. As Guterres recently stated, “Public resources from governments are simply not enough.” Achieving the SDGs would open an estimated $12 trillion in market opportunities and create 380 million jobs by 2030, significantly raising the standard of living for those at the base of economy pyramid.

It’s in private industry’s interest to spur sustainable development in poorer economies to seek no poverty by 2030—yet the UNDP estimates that only 10 percent of current SDG investments come from the private sector. With an estimated minimum of $5 trillion to $7 trillion in annual resources needed to achieve the SDGs, if corporations are truly committed to re-defining their purpose—heeding the advice of BlackRock’s Larry Fink to account for their corporate social impact—then they should step up to support SDG #1.

With this in mind, we must increase—and vary—investment in Africa. According to the World Bank, the majority of the world’s poor live in sub-Saharan Africa, where the poverty rate stands at 41 percent. In contrast with trends elsewhere, the total number of people living in extreme poverty in the region rose from 278 million to 413 million between 1990 and 2015. Businesses must focus on capital investment in this continent to catalyze growth. But with a heavy concentration of fintech deals and capital in Africa concentrated in just three countries (South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya), and the current financing gap to achieve the SDGs in Africa estimated at between $500 billion to $1.2 trillion annually, we urgently need to diversify investments.

Basic services are still out of reach for too many people

Second, we must prioritize quality and affordable basic services. For the world’s poorest people, reliable electricity, sanitation, health care, and education are all-or-nothing propositions. Nearly 1 billion people globally live without electricity, 2.3 billion people lack basic sanitation, and similar numbers go without proper healthcare or education.

Furthermore, without the financial services to render these life-enhancing products and services affordable, few can take advantage of them. 1.7 billion adults who remain unbanked, of whom more than half are women. Pairing basic-services access with financing can significantly strengthen a low-income business owner’s chances at economic mobility.

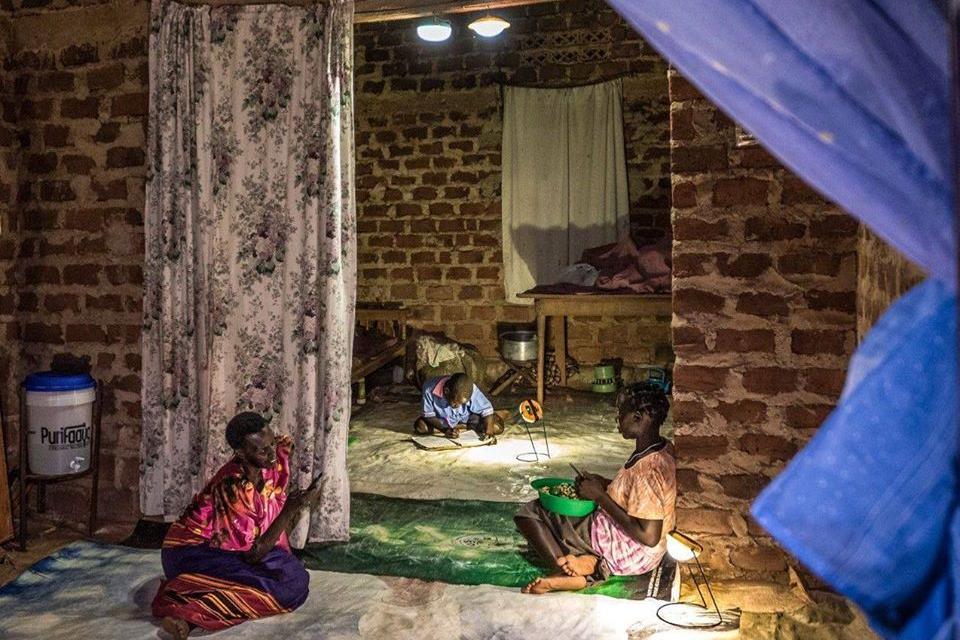

BrightLife, a social enterprise founded by FINCA International, demonstrates such a business model in action: This triple-bottom-line company, based in Uganda, makes clean energy products accessible through secure pay-as-you-go financing. BrightLife’s model builds credit profiles for unbanked populations while solving for essential challenges facing last-mile, off-grid customers (As shown in the above photo, which features a family that benefits from BrightLife's pay-as-you-go solar power service.).

Poverty is inextricably linked to climate change

Finally, we must raise the level of urgency among all stakeholders, including the general public. For wealthy countries, extreme poverty can feel overwhelmingly remote—both geographically distant and intractable. NGOs have a crucial role here: They can show their supporters how they can contribute to global poverty alleviation, and why they must. Greta Thunberg has demonstrated the power of a single activist voice in mobilizing widespread calls for climate action. Yet, poverty and climate change are inextricably linked. We must harness the energy behind the movement to end poverty in our lifetimes. Consumers must call on the companies they purchase from to actively help realize a world without poverty—or it simply won’t happen.

Despite the SDGs’ looming deadline, I’m not without hope. Ensuring that there is no poverty by 2030 is an addressable challenge, and the world has seen significant progress. Thousands of new social enterprises are springing up each year in the developed world and in emerging markets, and many have brilliant solutions to long-standing problems.

According to Nobel Laureates Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo, the average income of the bottom 50 percent of earners nearly doubled between 1980 and 2016. Since 1990, the population living in global poverty has fallen by more than 1 billion people, or by 26 percent. But we must cross the finish line—we must end poverty. To deliver on the vital vision laid out by the SDGs, within the next decade, the private sector must massively scale up far-reaching solutions, spurred by the public’s backing. At the dawn of this decade, there’s no time left to waste.

Rupert Scofield is President, CEO and co-founder of FINCA International. He is a pioneer in microfinance, a life-long social entrepreneur and an agricultural economist with over 40 years of experience in developing countries.