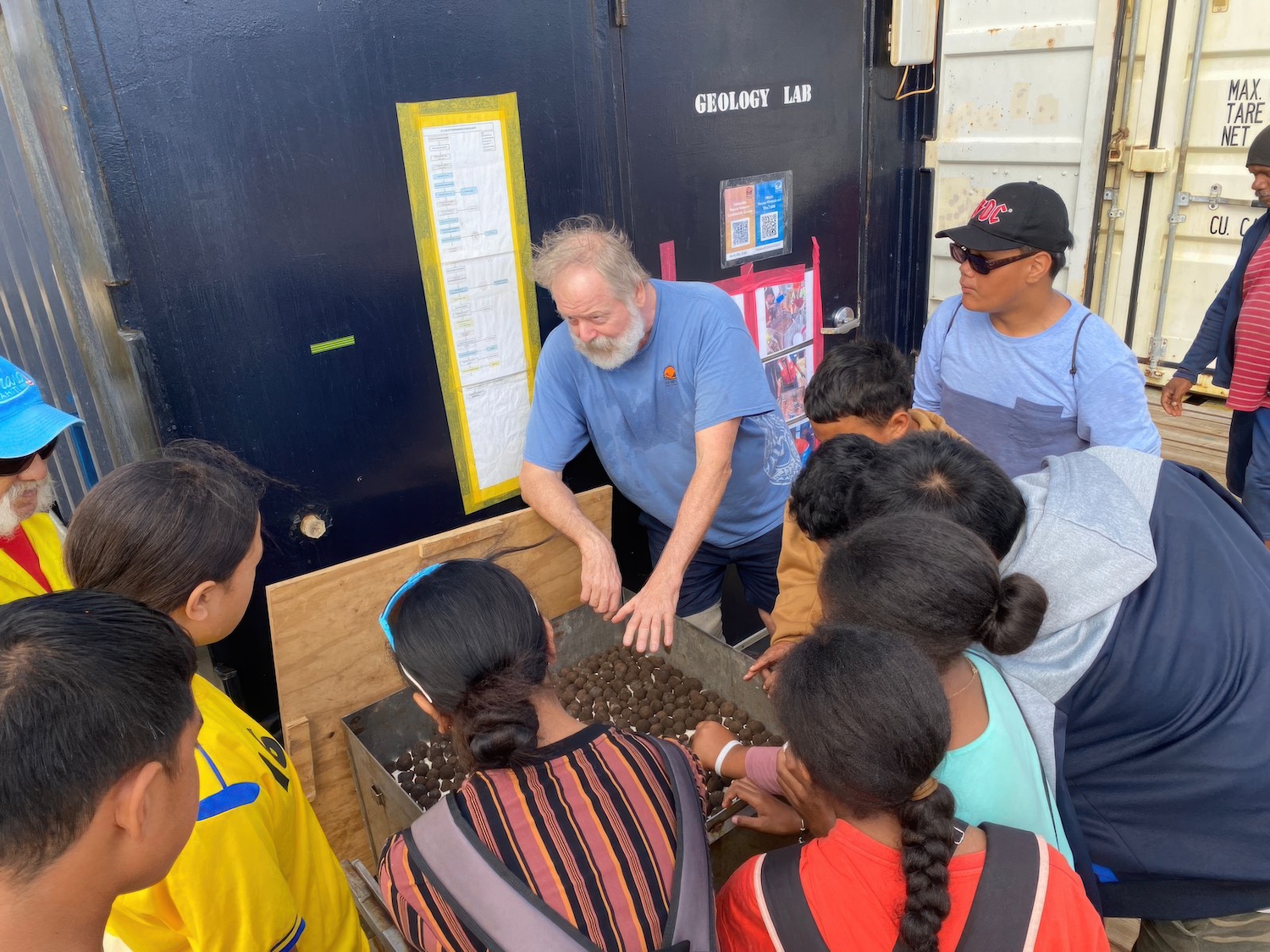

Community members from Mauke, an island of the Cook Islands, tour one of Moana Minerals deep-sea mining vessels. (Image courtesy of Moana Minerals Ltd.)

This article is part of our series on responsible mining solutions. The push for clean energy is fueled by a growing demand for minerals, but conventional mining has a track record of harmful social and environmental impacts. Deep-sea mining is another potential solution to that problem.

A tiny Pacific nation may become the first in the world to mine the ocean floor. The Cook Islands, about 3,000 miles east of Australia near Tonga and Fiji, lays claim to an enormous wealth of polymetallic nodules in its national waters.

Some Cook Islanders are excited about deep-sea mining’s economic potential, while others are worried its environmental impacts will be destructive and irreversible. Three companies currently have exploration licenses, but they are still years away from approval for any commercial mining activity.

“There are two primary objectives from a government perspective,” said Edward Herman, partnerships and cooperation director of the Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority, based on the main island of Rarotonga. “Can this be done in an environmentally acceptable manner? And is this economically feasible?”

Why the Cook Islands?

The Pacific island nation of 15,000 people is putting the finishing touches on a framework that may one day bring deep-sea mining to its exclusive economic zone, the area off the nation’s coast that it has exclusive rights to explore, use and manage. The majority of viable locations for deep-sea mining lie in international waters, but the 15 islands that make up the Cook Islands are home to about 6.7 billion metric tonnes of polymetallic nodules.

The manganese content of the Cook Islands’ nodules is estimated to be similar to the total known reserves of manganese on land. The cobalt, at a grade of about 0.5 percent, is the highest-grade cobalt in the world. And the nickel and copper content are significant. All four minerals are crucial to clean energy technologies like lithium-ion batteries, solar panels and grid storage.

The country awarded three different companies with five-year exploration contracts in 2022 to assess the nodule fields, gather baseline environmental information, and try to prove that mining the ocean can be done profitably and without significant negative impacts. The companies also need to convince Cook Islanders that this is an industry they want to be involved with. Locals, known to be friendly and very welcoming, are not quite ready to open their doors to this new industry.

“What I would like to do is empower people with information so they can make an informed decision,” said Hans Smit, CEO of Moana Minerals, one of the exploration license holders in the Cook Islands.

The Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority is gathering its own data in parallel to the mining companies and will determine, based on the data and environmental impact assessments, whether to allow mining in its waters.

The environmental unknowns

It might be controversial to say that deep-sea mining is less destructive than land-based mining, but at first glance, that appears to be the case. In deep-sea mining, large devices similar to vacuum cleaners essentially drop to around 3 miles below the ocean surface and scoop up the nodules lying atop the ocean floor. The process disturbs the sea floor to a depth of a couple of inches, as opposed to blasting, tunneling, and extracting tonnes of rock miles below the Earth’s surface and creating enormous quantities of waste, as in land-based mining.

There is also no need for tailings ponds in deep-sea mining, which means no potential for tailings dam breaches that wipe out entire habitats and towns, and no need to displace rural communities to make room for a mine.

The real issue with deep-sea mining is the unknown. Because relatively little research has been done in the deep ocean, it’s difficult to say with any conviction what the impacts may be, or what sort of knock-on effects seabed disturbance may cause in the rest of the water column and the planet’s natural cycles.

“We understand the government’s desire to improve the economy, but we’re concerned about seabed mining because we don’t know what the impacts will be,” said Kelvin Passfield, technical advisor at Te Ipukarea Society, a Cook Islands NGO. “We think it’s premature to think of digging up the seabed anytime in the next 10 to 20 years. We need a lot more research to be done.”

The social impact debate

The primary benefit of deep-sea mining for Cook Islanders would be the economic stimulus to the tourism-dependent nation. Tourism accounts for around 70 percent of the Cook Islands’ gross domestic product. If tourists stop coming, the country stops running.

“In 2020 when Covid hit, that was two years of tough times for the country,” Herman said. “We went from being a high-income country to close to no income.” Herman acknowledged that the pandemic catalyzed the nation’s search for diversification options, including deep-sea mining.

The government set royalties of 3 percent on the value of all nodules mined and mandates that any mining company be registered in the Cook Islands and pay tax on its profits. Based on these lines of direct revenue, Moana Minerals anticipates that between $50-100 million of annual government revenue would be generated per mining vessel.

The Seabed Minerals Authority is setting up a sovereign wealth fund modeled after Norway to ensure that all Cook Islanders benefit from any deep-sea mining income.

Additional economic boosts would come from local employment at the mining companies and ancillary businesses. Transportation crews, hospitality, supply vessels, maintenance teams, research units, and laboratories would all encourage young Cook Islanders to pursue a career at home, as opposed to the popular pathway of leaving home to search for work in Australia or New Zealand.

Not everyone is convinced by the promises of an improved economy, though.

“I don't think we would see any real economic benefit from seabed mining in the short term,” said Passfield of Te Ipukarea Society. “By the time the mining companies start recouping their investment, however much money gets down to the Cook Islands would be minimal.”

Passfield said he also doesn’t buy the employment boost argument, arguing that foreign workers will fill offshore positions just as they do on cargo and inter-island boats.

What do Cook Islanders say?

The pulse of the community is fairly split on whether they want deep-sea mining to go ahead in their country, Passfield said.

Smit, CEO of Moana Minerals, said he thinks the community is at about a seven out of 10, where 10 is in full support of deep-sea mining and one is completely against the idea.

On his recent consultation tour of the southern group of islands, citizens seemed most concerned about how the government will handle the extra income, Smit said. As his team accumulates more environmental data and presents it to the people, the community is warming up to the idea.

“Meetings started with people being very stern and frowning with arms crossed, but by the end of the evening, people had that usual Cook Islands joviality and everybody laughing,” Smit said. “Probably the most repeated comment was, ‘Make sure when you go mining and the money is flowing, that it doesn't just go into Rarotonga. Make sure the outer islands fairly benefit from it, too.’”

Andrew Kaminsky is a freelance writer with no fixed location. He travels all corners of the globe learning about the different groups that call this planet home, seeing natural wonders, and sharing laughs with the people he finds along the way. An alum of the University of Winnipeg's International Development program, Andrew is particularly interested in international relations and sustainable development. In his spare time you are likely to find Andrew engaging in anything sport-related, or finding common ground with new friends over a craft beer.