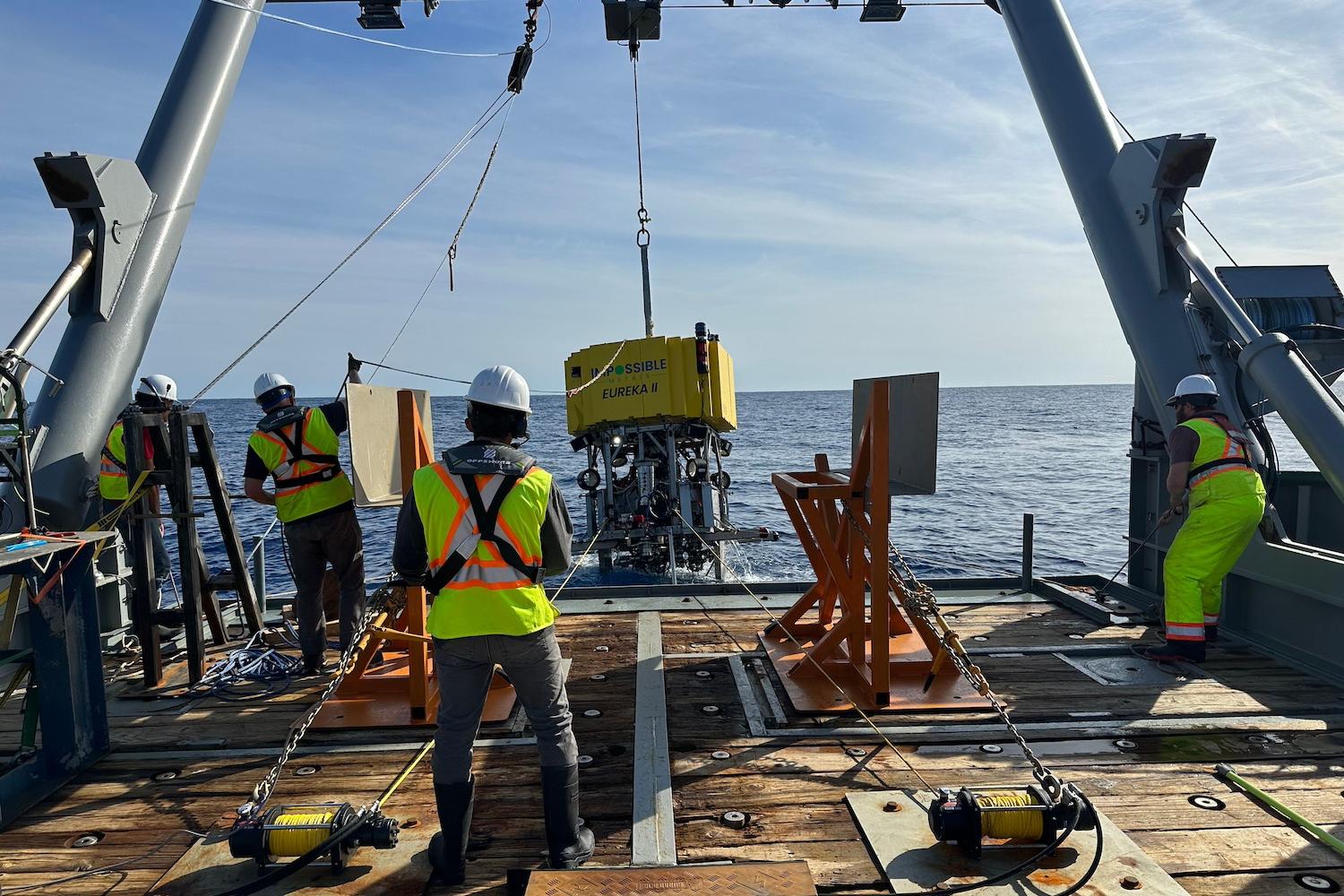

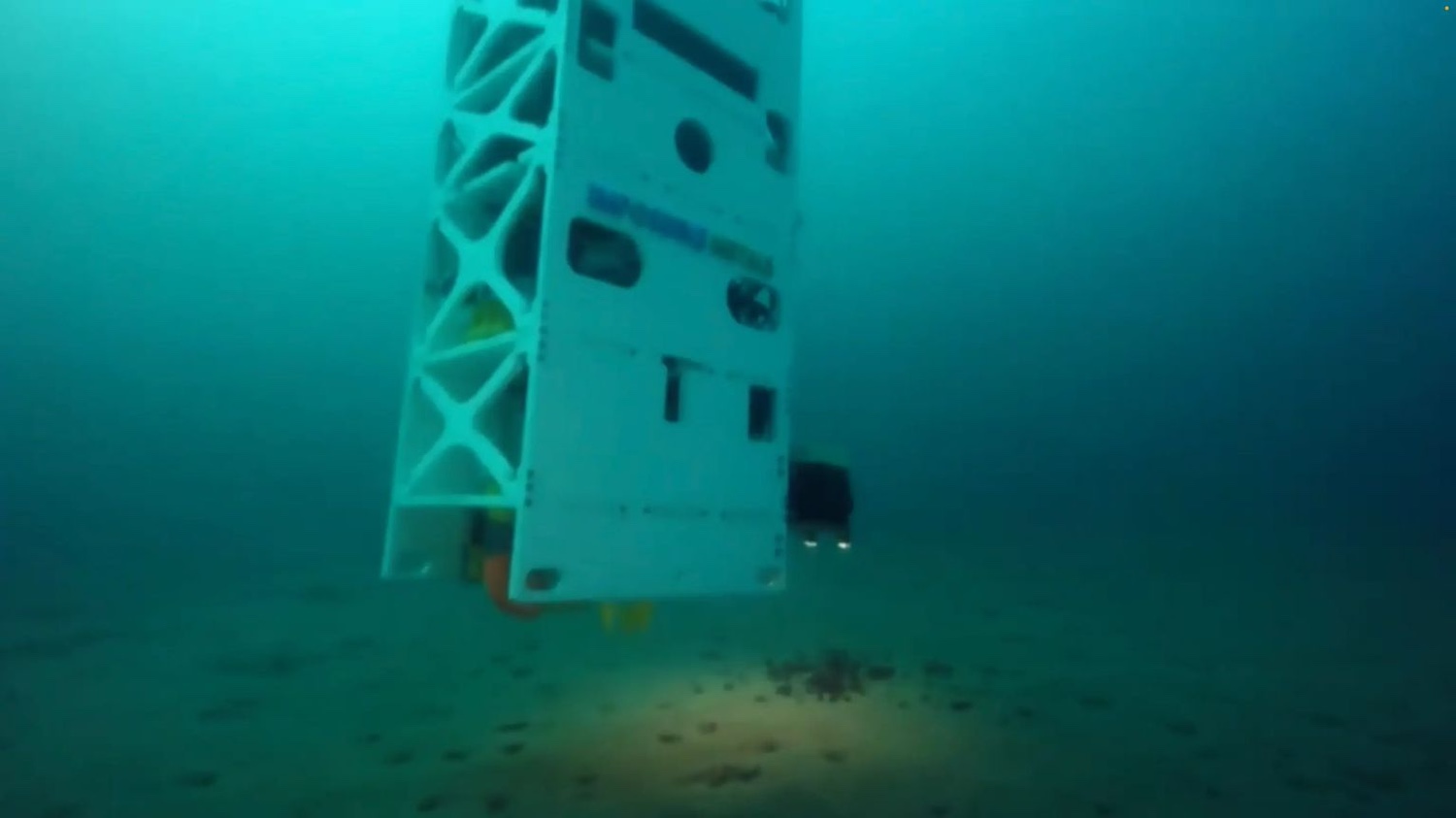

Impossible Metals lowers its autonomous vehicle the Eureka II into the water for a test in 2024. The machine collects potato-sized rocks on the ocean floor, a form of deep-sea mining. (Image courtesy of Impossible Metals.)

This article is part of our series on responsible mining solutions. The push for clean energy is fueled by a growing demand for minerals, but conventional mining has a track record of harmful social and environmental impacts. Experts are exploring whether deep-sea mining could be a solution to that problem.

“I'm not strongly anti-seabed mining, which surprises me,” said Elizabeth Mendenhall, associate professor at the University of Rhode Island and specialist in international ocean governance. “A lot of that is because those nodules are so readily available on the sea floor.”

Sitting atop the ocean floor are potato-sized rocks rich in copper, nickel, cobalt and manganese, all of which are in high demand and critical to clean energy technology like electric vehicle batteries, solar panels and wind turbines.

The Clarion–Clipperton zone, an area in the Pacific Ocean roughly half the size of the continental United States, contains higher quantities of nickel, cobalt and manganese than all land-based reserves combined.

Deep-sea mining has the potential to meet growing mineral demand, but an internationally coordinated approach is needed to ensure it is managed responsibly.

How does deep-sea mining work?

As of today, no commercial deep-sea mining operations exist, but many companies and countries are exploring its feasibility. There are three different types of deep-sea mining: cobalt-rich crusts, hydrothermal vents and polymetallic nodules.

Polymetallic nodules are the potato-sized rocks on the ocean floor, the most commercially viable and least environmentally damaging form of deep-sea mining. The nodules form over millions of years when metallic compounds settle on the seabed at depths beyond 4,000 meters (2.5 miles).

Collecting these nodules does not involve blasting or digging massive pits. An autonomous vehicle would crawl the ocean floor, suck up the nodules, and send them up a long pipe to a vessel on the surface to be taken for processing.

“The high grades of four metals and remarkably low levels of impurities in nodules mean it is possible to convert the entirety of a nodule’s mass into useful products,” said Rory Usher, senior communications manager at The Metals Company, one of the world’s largest deep-sea mining companies. That means mining each nodule would result in very little waste and multiple streams of revenue.

“When we bring up one ton of nodules, we are producing the equivalent metals of three or four land-based mines,” said Hans Smit, CEO of Moana Minerals, a company exploring polymetallic nodules in the Cook Islands.

The nodules are 37 percent metal, and the rest is a type of ore that can be sold as a metal or serve as aggregate fill, Smit said. To produce cobalt, for example, Moana’s operations would be, “as cost effective as the big cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or just slightly more expensive than them,” he said, pointing out that the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s cobalt mines are the most cost effective in the world but are clouded by human rights concerns.

What are the environmental and social concerns?

On the social side, deep-sea mining is an improvement over land mining. There are no people to displace, human rights to violate, or Indigenous land claims to disregard on the international seabed. And the financial benefits of international seabed mining are supposed to be shared with all countries, though the details are still being determined.

As for environmental impacts, it’s a matter of who you ask. “Is there an impact? Absolutely,” Smit said. “But it's certainly the least impactful method of collecting these metals that exists.”

To collect polymetallic nodules, no forests need to be cleared, no rock needs to be exploded, and perhaps most importantly, no toxic elements need to be introduced to extract the metals, meaning no tailings facilities and no tailings dam bursts. There is, however, a lot we still don’t know about the impact on deep-sea life.

“We’re trying to secure a moratorium on deep-sea mining so we can do the science and fully understand it,” said Travis Aten, communications and public campaign manager at the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition. “Some of the top deep-sea scientists say we need 10 to 15 more years of science first.” The coalition is one of several environmental organizations calling for a moratorium, including the World Wildlife Fund and the Sustainable Ocean Alliance.

Animals rely on the nodules as an attachment surface, anchor or shelter. The plumes kicked up from collection vehicles, and the noise and light, could disturb the environment. And a recent study suggested that nodules might produce oxygen via electrolysis in the deep ocean, though the validity of this claim is contested.

“All that shows is that, again, we have so much to learn about the deep sea still,” Aten said.

Research shows that the density of life on the sea floor is low and mostly microbial. But some animals, like sponges, corals, sea cucumbers, and octopuses, have been recorded at the nodules.

Some miners are taking steps to address environmental concerns. “Our AI hovering robot is looking for life. If we see life on the seabed, we create a quarantined virtual area and don't disturb anything within the area,” said Oliver Gunasekara, CEO of Impossible Metals.

Who governs the deep sea?

Countries have exclusive rights to ocean resources up to 200 miles past their coastline. Beyond that, it’s international waters. The organization that regulates deep-sea mining in international waters is the International Seabed Authority, which receives its mandate from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, signed and ratified by 168 parties. The authority has not yet developed deep-sea mining regulations, something that frustrates a wide variety of stakeholders. Notably, the U.S. never ratified the Convention on the Law of the Sea treaty. In April, U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order aimed at expediting deep-sea mining permits, a move criticized by several countries.

Elizabeth Mendenhall, an expert on the treaty, explained that three things make the International Seabed Authority negotiations difficult. First, it’s hard to negotiate international agreements. Second, major scientific uncertainties exist around environmental impacts. And third, some form of equitable benefit sharing needs to be agreed on.

Miners want regulations in place now so they can apply for mining licenses, something they haven’t been able to do yet.

“What we need to do is get to a point where, assessing the data that we have, we can move forward applying processes like adaptive management,” Smit said. “As we move forward and we learn more, we keep that feedback loop going and we continually improve. Should we get to a position where what we are doing becomes untenable, then we stop. To be paralyzed with inaction is detrimental across the board.”

The next International Seabed Authority assembly is set for July 2025.

Andrew Kaminsky is a freelance writer with no fixed location. He travels all corners of the globe learning about the different groups that call this planet home, seeing natural wonders, and sharing laughs with the people he finds along the way. An alum of the University of Winnipeg's International Development program, Andrew is particularly interested in international relations and sustainable development. In his spare time you are likely to find Andrew engaging in anything sport-related, or finding common ground with new friends over a craft beer.