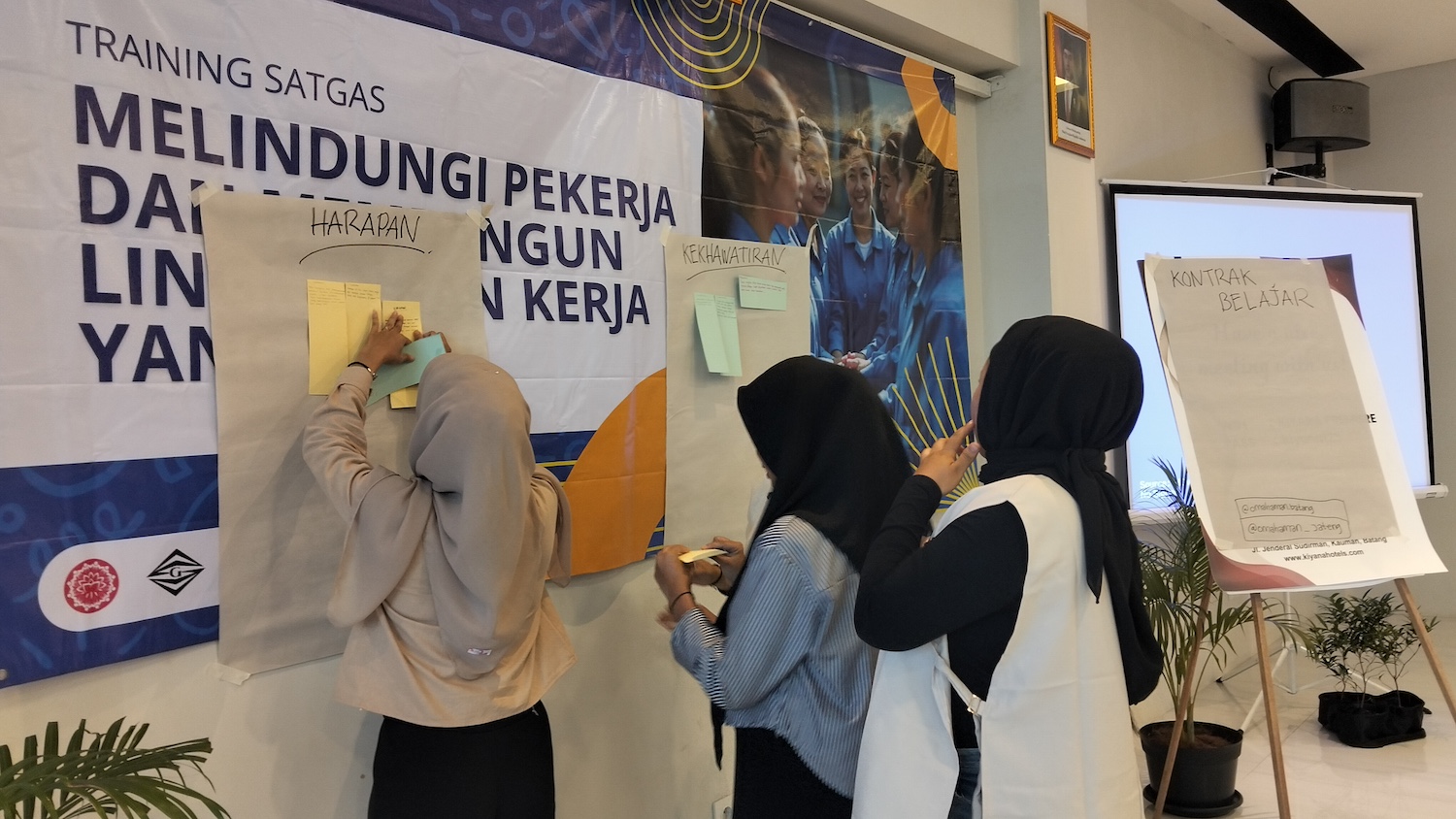

A task force training that's part of the education, monitoring, and enforcement system created by the gender justice agreement implemented at at two garment factories in Indonesia. (Image courtesy of Workers Rights Consortium.)

For women workers in Indonesia, a landmark gender justice agreement signed last year promises real change at two garment factories employing over 6,000 workers. It aims to eliminate gender-based violence through a union-led program, with independent accountability and real threats for noncompliance. If factories fail to comply, they will lose access to key buyers, including Western brands like Fanatics and Nike.

“This agreement is proof of the power of workers to get a comfortable and safe workplace,” said Sekar, who is a union leader at one of the factories included in the agreement, PT Batang Apparel Indonesia, and like many in Indonesia, uses a single name.

Sekar and others hope this unique partnership of labor unions, nonprofits, and businesses can expand and improve working conditions for more of the estimated 4.3 million workers in this growing Indonesian industry, a majority of whom are women.

“We have plans to expand this program to other companies as a pilot in Central Java based on practices that have been carried out at both companies,” said Turyana, a union leader at PT Semarang Garmen, the other factory included in this agreement.

Violence with no accountability

For years, women workers in garment factories in Central Java, Indonesia, have faced harassment, gender-based violence, and other workplace issues daily. They aren’t isolated incidents, they are part of a toxic workplace culture.

An investigation at both factories in 2022 led by the nonprofit Workers Rights Consortium found that “women workers were being touched without their consent, subjected to sexual comments and demands, verbally abused, and being pressured to give ‘gifts’ to factory personnel.”

Moreover, the investigation found that managers were not only failing to address abuses when they were reported, but were often complicit themselves. Factory owners in South Korea and buyers of garments in the United States and Europe were completely unaware that such abuses were taking place at their key suppliers.

These factories are owned by OnTide, a Korean company that supplies products for brands including Fanatics and Nike. None of them were aware of the issues that women workers faced from local factory managers, which shows a failure of monitoring and auditing in their supply chains.

“Upon learning of these troubling allegations, we moved quickly to terminate or otherwise discipline numerous individuals found to be involved in inappropriate behavior,” John Yoon, OnTide’s sustainability director, told Triple Pundit.

Once OnTide was alerted of the problem by Workers Rights Consortium, it acted with the urgency and responsibility one would expect from a values-driven business.

The role of buyers

Of course, reacting to allegations is the bare minimum. Ensuring that abuses end through systematic change in operations and oversight is what can make a real difference. That’s why Workers Rights Consortium and the various unions representing workers at the two factories ultimately wanted to create a framework to prevent such abuses from ever occurring.

The agreement is expansive, focusing not only on disciplining perpetrators but also creating a system of education, monitoring and enforcement — all with workers playing a leading role. The goal is to ensure everyone better understands their rights and responsibilities to prevent gender-based violence in the workplace. Moreover, it aims to create channels for communication that workers trust, as crimes often aren’t reported due to fear or disempowerment.

“This agreement is a model for how the industry can address the workplace assault and harassment that is the daily reality for too many garment workers around the world," Jessica Champagne, deputy director at Workers Rights Consortium, said in a press statement.

To do that, OnTide needed to play a key role. Union leaders, workers, and the consortium all noted that this agreement and its scope would not be possible without buy-in from the businesses at the other end of the supply chain.

“We worked closely with our buyers, the Workers Rights Consortium, local trade unions, and other stakeholders to develop a comprehensive remediation plan that will provide a safe and secure work environment for all employees,” Yoon said.

This led to active support from managers, who were facing pressure from OnTide to create a fair agreement that protected women workers.

“From the management side, there was no rejection, resistance or pushback,” said Dede Erwanto, also a union leader at PT Batang Apparel Indonesia.

Still, it took more than a year to figure out the best way to protect women, distribute financial resources, and implement effective grievance and accountability mechanisms. It was uncharted territory, as no such agreement exists anywhere for the millions of garment workers in Southeast Asia.

One thing that workers like Dede, Turyana, Sekar, and others wanted was worker oversight. That means labor unions, not factory owners, would be in charge of ensuring the agreement is upheld.

“This agreement is proof of the power of workers to get a comfortable and safe workplace, as their rights have been successfully fought,” Sekar said.

Better workplace, better productivity

Since the agreement came into force in mid-2024, women workers at both factories have seen a marked improvement in working conditions, with less harassment and verbal abuse.

“It’s impacted the livelihoods of workers with better physical and mental well-being, as well as increasing positive job satisfaction,” Egye Gumilang, a union leader at PT Batang Apparel Indonesia, told TriplePundit.

It also led to workers being more engaged, happy, and, in what shouldn’t come as a surprise, better productivity.

“Higher work enthusiasm and a greater sense of belonging to the company among workers has ultimately increased productivity,” Dede said.

While the significance of this agreement is commendable, it is just a drop in the bucket. Local labor unions, nonprofits, and Workers Rights Consortium are aware that, across Central Java and other provinces in Indonesia, women workers are likely facing sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence and hope to see this model spread across the country.

“We can see an opportunity for expansion to other factories that have the same level of risk of violations,” Sekar said. “This agreement can be successfully replicated in a way that leads to improving the conditions of other factories.”

When owners and those along the supply chain are willing to listen to workers and collaborate on solutions, the outcomes can benefit all parties. As Indonesia expands as a manufacturing center and more women enter the workforce, this agreement shows the benefits of creating worker-led systems to prevent harassment and sexual abuse and ensuring a safe workplace for all.

Editor's note: This story was updated on June 2, 2025, to more accurately reflect the investigation led by Workers Rights Consortium in 2022.

Nithin Coca is a freelance journalist who focuses on environmental, social, and economic issues around the world, with specific expertise in Southeast Asia.