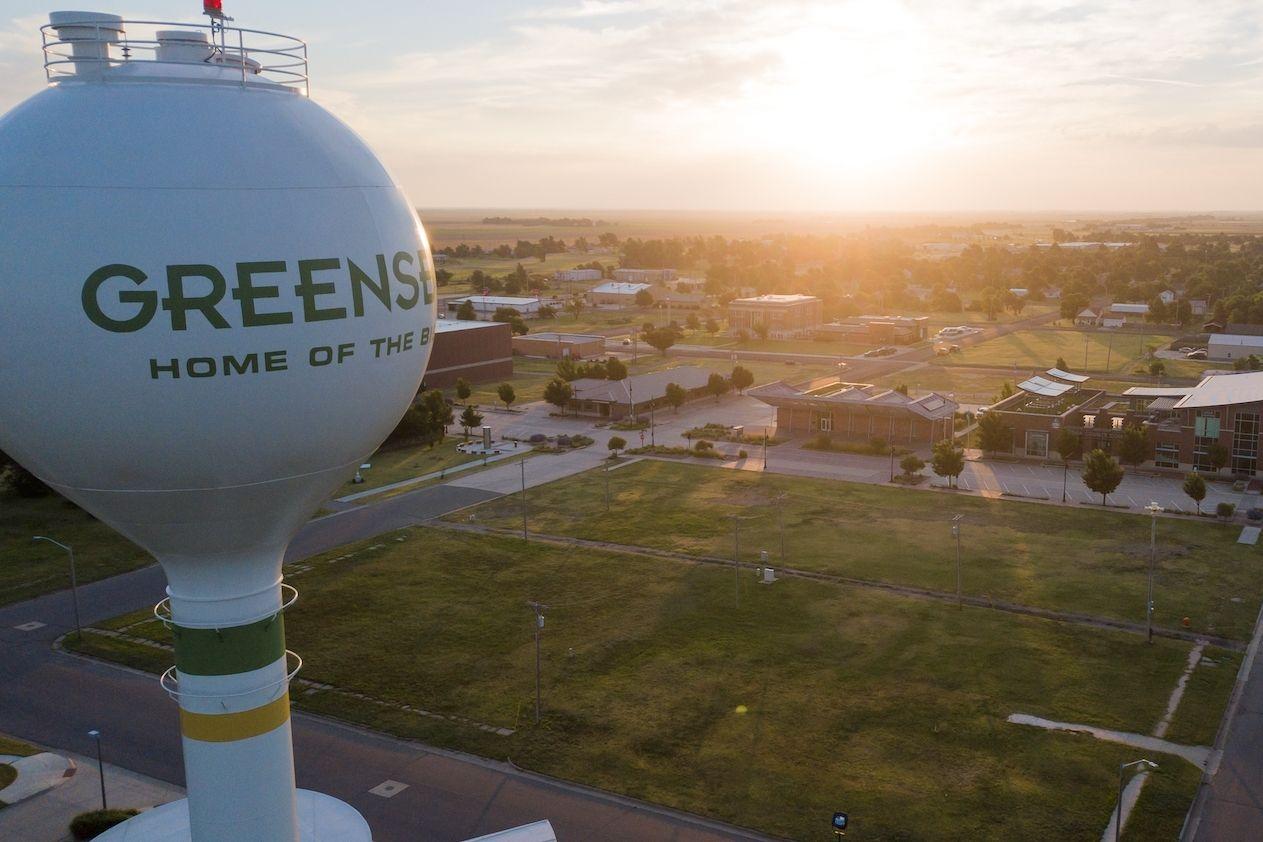

(Image courtesy of Kiowa County Media Center.)

In May 2007, a catastrophic tornado nearly wiped Greensburg, Kansas, off the map. Instead of simply rebuilding, the town chose to reinvent itself. Today, the community is regarded as one of the greenest towns in the United States, drawing 100 percent of its municipal power from wind energy, constructing every public building to meet the highest level of LEED green building standards, and embracing a culture deeply rooted in conservation.

“When your entire town is destroyed and your life upended, you’re faced with a choice,” City Administrator Stacy Barnes, a lifelong Greensburg resident, told TriplePundit. “For most people here, this is home. They wanted to rebuild, not just because it was necessary, but because they love this place.”

The town’s path forward was shaped by its agricultural roots and resourceful ethos. “Greensburg is a very agricultural-based community. The land has always been a big part of our identity,” Barnes said. “That mindset influenced how we rebuilt: being mindful of conservation, energy use and fiscal responsibility. It was about doing more with what we have.”

That conviction was central to the town’s decision to embrace sustainability. “Our conservative values, especially conservation, really informed our choices,” Barnes said. “Being efficient and saving money matters to people here. Energy-efficient homes, better windows and insulation, water-saving fixtures — all of that made sense.”

To guide its efforts, Greensburg developed a sustainable master plan in partnership with a planning firm that facilitated community engagement so residents could have a say.

“When you’re rebuilding almost from scratch, you need a roadmap,” Barnes said. “The process allowed residents to dream big.”

Today, Greensburg powers all municipal operations with 100 percent wind energy through a long-term agreement with a nearby wind farm. Smaller-scale turbines once dotted the town, but maintenance proved costly, and the turbines were eventually phased out.

Some buildings, including the city hall, also have solar panels. Greensburg is now partnering with the not-for-profit energy agency KPP Energy to build a one-megawatt solar farm at its business park.

Water conservation is also ingrained in everyday life here. Greensburg sits atop the Ogallala Aquifer, one of the nation’s most stressed groundwater sources.

“New construction uses low-flow fixtures, and we’ve planted native grasses downtown that require less water,” Barnes said. “Some residents also use rain barrels. We’re not in a crisis, but we’re definitely mindful.”

Despite its sustainability focus, Greensburg doesn’t impose specific green building mandates. Instead, economic logic drives most decisions.

“We don’t have mandates,” Barnes said. “But most people choose to build efficiently because it just makes financial sense.”

Rebuilding a community is never just about infrastructure — it’s about relationships, compromise and perseverance, she said.

“People were dealing with the loss of homes, jobs, schools, churches — every part of life,” Barnes said. “Everyone wanted a thriving town, but how to get there varied. It took a lot of discussion and cooperation.”

That spirit of collaboration remains a defining feature of life in Greensburg. “We look out for each other. After the tornado, that spirit really showed,” Barnes said. “Even now, if someone’s going through a hard time, people step up to help.”

Nevertheless, change hasn’t always been easy. Balancing outside input with the town’s traditional values was essential.

“With all the outside help that came after the tornado, we had to balance innovation with staying true to who we are,” Barnes said. “I think friendliness and hospitality are part of our rural Kansas identity.”

The local sustainability conversation has also evolved, she said.“As we move further from the tornado, sustainability isn’t talked about daily anymore. It’s just how we live,” Barnes said. “But there’s always room to reengage and involve the next generation. It has to be an ongoing effort.”

Many residents who left after the tornado did not return. In 2000, Greensburg’s population was just under 1,600. Today, the town’s population hovers around 758. Even so, Greensburg’s reputation extends far beyond western Kansas. Communities from California, Kentucky, and elsewhere in Kansas turned to Greensburg for guidance following their own climate-related disasters.

“We’re always happy to share our experience,” Barnes said. “Every situation is different, but we try to pay it forward, sharing what we learned and the support we received.”

As 2027 marks the 20th year since the tornado, Greensburg remains focused on steady, incremental progress. “People ask if we’re done rebuilding. The answer is no,” Barnes said. “No community is ever done. There’s always room for progress.”

The next step may not involve a sweeping new plan, but rather the everyday choices residents make: to use less water, build smarter or lend a hand to a neighbor.

“You make the best decisions you can at the time and move forward,” Barnes said. “And that’s key. Just keep moving forward, even if the steps are small.”

Gary E. Frank is a writer with more than 30 years of experience encompassing journalism, marketing, media relations, speech writing, university communications and corporate communications.